艾晓明 王西麟 | 谁是黑衣人?——关于王兵纪录片《黑衣人》与鲁迅小说《铸剑》(中英文)

编者按:艾晓明与作曲家王西麟隔空对话的这一组文章,涉及到三个文本:一、鲁迅的小说《故事新编》里的《铸剑》;二、王兵以王西麟为主角的纪录片《黑衣人》;三、王西麟根据鲁迅作品创作的歌剧《铸剑》。如果深入探讨的话,其中的互文关系就更复杂了,鲁迅的《铸剑》最初发表于1927年,《铸剑》的故事来源,有关春秋时代眉间尺复仇的传说,成书时间到现在,差不多有一千九百多年。一个公元前几百年传说中的人物,在21世纪仍然被演绎,那故事里,究竟隐藏了什么魔力呢?继鲁迅的文学改写九十多年后,王兵和王西麟分别用影像和音乐的语言各自诠释,构成了一场跨世纪的文本接力;从这一组对话中,我们再度逼近了今天这个世代依然要面对的主题,关于苦难、正义和义无反顾……

谁是黑衣人——关于王兵纪录片《黑衣人》与鲁迅小说《铸剑》

艾晓明 王西麟

图1 海德堡“声音论坛”网页

https://klangforum-heidelberg.de/veranstaltung/freiheit-i-betriebswerk-heidelberg-11-oktober-2024-20-00

有关鲁迅《铸剑》,研究文章相当多,下面这组文章是我在看王兵纪录片《黑衣人》前后和王西麟老师在微信上的一些交流。内容涉及到对鲁迅原文的理解、观看纪录片的感受和王西麟老师的创作缘起。10月11日,在德国海德堡,“声音论坛”将举办王西麟和德国韩裔作曲家尹伊桑作品的音乐会,活动中还将放映和讨论《黑衣人》。我把自己的文章和王西麟老师的交流编辑在一起,权且作为参与讨论的形式,也供有兴趣的读者继续探讨在这种跨世纪、跨艺术的文本改写里那撼人心魄的精神底蕴。这一组文章包括:

一.艾晓明:《谁是黑衣人》

二.《对话:“人的躯体是一切苦难的承受者”》(包括艾晓明:《裸体的<黑衣人>——灵魂的胜利》和王西麟回信《“人的躯体是一切苦难的承受者”——致艾晓明谈<黑衣人>》)

三.王西麟:《歌剧<铸剑>作者的话》

王西麟老师准备将这些文字收入他的歌剧总谱,因此请朋友帮忙做了英文翻译。非常感谢译者Leo Timm奉献的时间精力和他准确优雅的文笔。我将他的译文附在每篇文章后面,以便和英文读者分享。

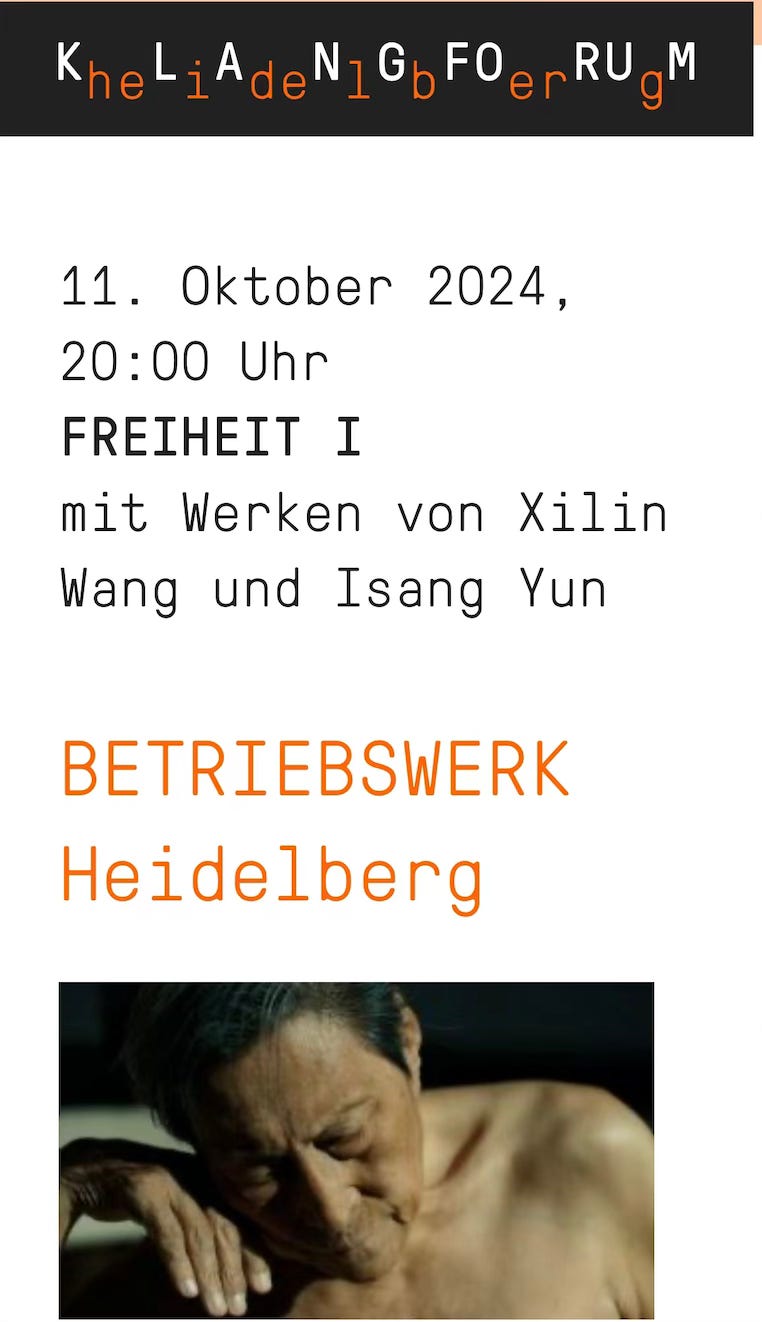

图2 王西麟老师在德国(我没有见过王老师,因此没机会拍摄他的照片,文中有关王老师的照片,来自他的亲友以及他从微信上传给我的图片,未能全部署名,特向拍摄者致谢)

图3 王兵与王西麟在巴黎的拍摄现场,2022年5月27日,周晓霞摄。

一 艾曉明:誰是黑衣人?

王兵先生完成了有关中国音乐家王西麟先生的纪录片《黑衣人》,为中国人留下了一个真实而强悍的艺术家形象。王西麟老师裸体出演,彷如时光雕塑,在中国纪录片的历史上,多么宝贵!

读了周晓霞老师转来Jessica Kiang的影评,觉得一切都写得很好,只是未提及“黑衣人”的寓意,略感遗憾。

“黑衣人”的形象出自鲁迅《故事新编》中的小说《铸剑》,王西麟曾为根据这篇小说改编的电影《铸剑》(导演:张华勋,出品/监制徐克,1994),写过“三头釜中舞”和“黑衣人歌”,在那部影片中,“黑衣人歌”的插曲就是王西麟自己唱的,钢琴伴奏者也是他本人。在王兵的纪录片《黑衣人》中,那挺立在银幕中,在旋转的镜头中静默如铜像般的身体,还有随即响起的歌声,就是这首“黑衣人歌”。

我下面要说的不是影片的内容,而是说为什么影评人不应错失这“黑衣人”的寓意。

黑衣人的故事基于中国古代有关眉间尺复仇的传说,鲁迅在此基础上写成小说《铸剑》。其中主角本是一个十六岁的少年,他并非生来孤勇,看到死老鼠都会害怕。但他在那夜从母亲那里得知父亲之死的真相和母亲的期待,从而领悟了为父报仇的天命。孩子穿青衣,提一把父亲留下的雄剑踏上征途,这是他的成人礼。可他走入市井,小混混都要欺负他,哪有本事替父报仇?正是在这时,他遇到了黑衣人。

这黑衣人,一要他的剑,二要他的头。

黑衣人是谁?是他父亲的同辈、同党、同仁、同性恋人?可能都是。而黑衣人说,我不是因为认识你和你的父亲才报仇。从他的自白里可以这样理解,他自己就是一个复仇者——他是反抗者,他拥抱一切反抗者,他与被屠杀的牺牲者不可分割,他是他们之中的一个。作为大屠杀的幸存者,他背负了不可抗拒的复仇使命。为什么他说他憎恶了自己,也许他内心背负了羞愧——道德的自律:在牺牲者之上无法苟活的羞愧,这是他所说的人我所加的伤——来自仇人,也来自内在的自我。

这个人物,是鲁迅在传说基础上的一个创造,我们也可以说,这个人或许不是别人,而是眉间尺的另一个自我,他代表完美的勇者人格,是眉间尺内心分裂出的另一个人。他们之间形成了对比:一个弱,一个强;一个幼稚,一个成熟;一个初出茅庐,一个久战疆场;一个还怀有很多对生命的不确定,另一个已生无可恋,一心赴死。

少年眉间尺啥话不说,居然就举剑削头,提剑予黑衣人。这纯真的、义无反顾的牺牲是让人错愕的。在鲁迅小说里,这是我们不熟悉的少年,他单纯,为了信仰,不惜以身取义。黑衣人则是另一种力量,蓄谋已久,可能之前已不知经历了多少挫折和败战,但积蓄了潜能,找对了新血。

在这里,从鲁迅的叙事技巧来说,主人公一刀毙命,故事还怎么写?《铸剑》的新意却在这里,无头的少年没有消失,它成了通向王宫的计谋。这头颅失去了身躯却没有失去战斗力,它变成一个魔幻的象征形象,它是复仇天使、人劍合一的亡灵勇士。可是它需要另一个人物的智慧才能进入战斗,这个智者就是黑衣人。

从象征意义来看,黑衣人承受了无边的黑暗和苦难(我不禁想起鲁迅的诗句:“万家墨面没蒿莱,敢有歌咏动地哀”)。黑衣人的生命中,蕴含了了数代人的冤屈和反抗者的热血。他方生方死、若死若生;死者和生者的界限在他这里模糊了,或者说跨越了——因为他的生命里都是他们,他要为他们而慷慨赴死,使后世的少年得以存活。

所以他有一个仪式,那就是吻向那少年人断头的唇。这是爱的欲望,也是断绝;是前辈对于弱小者、赴死者对于永生者的诀别。在鲁迅的小说里,这个画面是忆念也是断念,一吻再吻,上路。鲁迅用了三次“扬长地走去”来描绘黑衣人,这正如古诗中所吟唱的:“风萧萧兮易水寒,壮士一去兮不复还!”猛士坦荡上路,天地失色。

王西麟老师吟唱的黑衣人歌,就是在这时响起的:

哈哈爱兮爱乎爱乎!

爱青剑兮一个仇人自屠。

夥颐连翩兮多少一夫。

一夫爱青剑兮呜呼不孤。

头换头兮两个仇人自屠。

一夫则无兮爱乎呜呼!

爱乎呜呼兮呜呼阿呼,

阿呼呜呼兮呜呼呜呼!

国王此时高坐殿中,这是个虐待狂,玩剑杀人,还是百无聊赖。黑衣人进殿,禀报少年头可在金鼎沸水中曼妙起舞,为君解闷消愁。

少年头扔进去了,没动静;君臣大怒,恨不能把黑衣人也掀进去。黑衣人歌声再起,那少年头也唱起来,歌声弱下时,君王立在鼎边,与头对视,似曾相识;说时迟那时快,黑衣人剑起头落。干得漂亮!

《铸剑》的叙事高潮是在此后,少年头与大王头来回鏖战,殊死拼搏。哎,都死定了,还拼什么?要拼,要压倒暴灵,要他永不能复活。这个有点像但丁的《地狱》篇了,生前的人们在死后相遇,灵魂不灭,但是灵魂之间,正义与邪恶的争战在继续。

然而少年不敌老贼,连金鼎外面也听到孩子失利的号叫了。黑衣人此时从容赴死,劈头入鼎。死后的三头大战,难解难分,至死不休直到体无完肤,同归于尽……这风华绝代的鏖战,惊天地,泣鬼神!大王呀,你再也不要想水晶棺的事!

鲁迅的原作,发掘了传说故事中反抗的精神,创造性地描绘了黑衣人的形象,使之成为反抗者智慧与勇气的化身。《铸剑》的故事,昭示了苦难记忆的承传和殊死反抗的理想。那割头献祭的形象,在西方的宗教艺术作品中也有,但鲁迅写的没有宗教色彩,他笔下的三头鏖战,呈现的是除恶务尽、义无反顾的境界,惨烈、悲壮,快意!

《黑衣人歌》开始的音乐略有诡异,王西麟唱得深沉委婉;继而有更饱满高昂的能量注入,我想起《悲惨世界》里的那首名曲:你可听见人民在歌唱!《铸剑》的音乐里有很多民间元素的加入,构成乐曲里的叙事性,也带来戏剧冲突。乐曲粗犷激越,音乐家的奇思加上民间打击乐的异响,使人感受到那种中国传统艺术里保留的原始的生命力。

所谓壮怀激烈,只有王西麟这样历经沧桑的生命才能诠释啊。与之比较,那些流行的红色经典,不过是各种意义上的媚声、没有灵魂的旋律。

王西麟老师的《三头釜中舞》我也听了,这样复杂激越的作品是需要反复听才会有更多的理解的。初步的印象是非常激烈的鏖战,远古的神话通过现代感的音乐表达出来。也许,熟悉中国文本的人会想起《铸剑》里老谋深算的野性,胜券在握、决死一战的意志,扬长再三、侠肝义胆和民间刀客的爆发力。

普通的中国观众,不一定知道鲁迅的《铸剑》,国外的观众知道的可能更少。只是,如果联想到经典的互文关系,想必更能理解王西麟的深意,他用作品向鲁迅致敬,向中国民间的反抗传统致敬。设想在演出现场,观众听到那些不和谐音,由此想到中国、中国人一代又一代的牺牲和苦难,会不会感到惊心动魄?而被这令人血脉贲张的激响所环绕,人们会不会想到,有一天,中国人的精神将从沉默中爆发,一种失之久远的魂魄将要复活……王西麟是在为民族精神造血而创作啊。

感谢王西麟,祝福王西麟/周晓霞老师,祝贺王兵完成大作!

2023年9月6日

图4 王西麟与王兵,结束拍摄后的庆贺,2022年5月28日,周晓霞摄。

图5 少年王西麟,摄于1948年。

Who Is the Man in Black?

— Rereading Lu Xun's ‘Forging the Swords’

Ai Xiaoming,Translated by Leo Timm

Wang Bing (王兵) has completed his documentary film The Man in Black (《黑衣人》) on the Chinese musician Wang Xilin (王西麟), leaving the Chinese audience (though they could not see this art piece right now) with an authentic and strong image of the artist. Wang Xilin’s nude appearance on the screen is like a sculpture of time. How valuable it is in the history of Chinese documentaries!

I read Jessica Kiang's review on the film, which was forwarded to me by Ms. Zhou Xiaoxia (周晓霞), the translator of the review to Chinese. I thought it was all very well written, except that Kiang did not address the symbolism of “The Man in Black,” which was somewhat amiss.

The character of the “Man in Black” comes from the short story “Forging the Swords” (《铸剑》) in Lu Xun's Old Tales Retold (《故事新编》). For the 1994 film adaptation of the story, directed by Zhang Huaxun and produced by Tsui Hark, Wang Xilin composed “Dance of Three Heads in the Cauldron” and “Song of the Man in Black.” He even personally performed the vocals and piano for “Song of the Man in Black.” In Wang Bing's documentary The Man in Black (《黑衣人》), we see Wang Xilin’s nude body upright and silent as a bronze statue as the camera rotates about him; the song that followed is “Song of the Man in Black.”

What I’m about to discuss is not the content of the documentary itself, but rather why film critics should not overlook the symbolism of the "Man in Black."

The story of the Man in Black is an ancient legend of a man named Mei Jian Chi (眉间尺) seeking revenge for his father, on which Lu Xun based his story “Forging the Swords.” The protagonist is a 16-year-old youth, by nature so timid that he is afraid of seeing a dead rat. But on a fateful night, he learns from his mother the truth of his father’s death and her expectations of him. Understanding his destiny lies in avenging his father, the boy, dressed plainly and armed with the magic sword his father left behind, embarks on his journey, his rite of passage. But as he steps into the real world, he is challenged by hooligans, not having the wherewithal to avenge his father. It is then that he meets the Man in Black.

The Man in Black asks for two things. One is Mei Jian Chi’s sword, the other is his head.

Who is the Man in Black? Is he his father’s peer, comrade, friend, or perhaps even his lover? He could be any or all of these. But he says, "I am not seeking revenge because I knew you or your father." From his confession, we can understand that he himself is someone who pursues revenge for its own sake: he is a rebel who embraces other rebels, and becomes inseparable from the massacred victims. As a survivor of the massacre, he bears an irrefusable mission of vengeance. When he says that he loathes himself, perhaps it’s because he carries internal shame — the moral self-chastisement of living with the unbearable guilt of having survived where others perished. This shame, as he describes, is at once something inflicted by his enemies as well as something that stems from his own inner torment.

It’s a character of Lu Xun’s creation. The Man in Black, it can be said, is perhaps Mei Jian Chi’s alter ego, split from his inner self that embodies the personality of a perfect hero. A contrast forms between them: one is weak, the other strong; one is naive, the other sophisticated; one is a novice, the other a battle-hardened warrior; one is uncertain about many things in life, the other has nothing else to live for than the single-minded pursuit of his fatal mission.

The young Mei Jian Chi says nothing, and raises his sword to behead himself, offering it to the Man in Black. This pure and resolute sacrifice is startling. This is no longer the youth Lu Xun introduced to us in the beginning — he is simple, and for the sake of his belief, he does not hesitate to sacrifice himself. The Man in Black represents another kind of strength, one that has been long in the making. He has faced god only knows how many setbacks and defeats before. He has tapped into a well of potential, and is now infused with new blood.

How would the story continue if the protagonist dies with a single stroke of the sword? Here lies Lu Xun's narrative ingenuity: the headless youth does not disappear, but becomes a stratagem for entering the palace. The severed head, while no longer attached to the body, has not lost its combat power; it transforms into a magical being, a vengeful angel, a ghostly warrior where man and sword are one. But it needs the wisdom of another to enter the battle: the Man in Black.

Symbolically, the Man in Black has endured boundless suffering and despair (I cannot help but think of Lu Xun's verse: "The gaunt-faced commoners are buried by weeds;None dares to sing a dirge to move the earth to grief."). A hot-blood rebel, his life carried with it injustices of generations. He is both the living and the dead, transcending the boundary between the two, for his life is filled with them, and he must die for them so that future generations of youth may live.

Therefore, he performs a ritual — kissing the severed lips of the young man. This is a kiss of love and desire, but also of severance; it is the farewell of an old to the young, of the martyr to the immortal. In Lu Xun’s story, this image represents both remembrance and the breaking of ties — a kiss, and then another, before setting out on the journey. Three times Lu Xun uses the phrase "walked away in long strides" to describe the Man in Black, just like the ancient verse of the assassin Jing Ke (荊軻): “The wind howling, the Yi River frozen, the hero is gone, never to return." Here too, the warrior strides away, leaving the world between heaven and earth pale behind him.

The “Song of the Man in Black,” sung by Mr. Wang Xilin, arises at this moment:

Sing hey, sing ho!

The single one who loved the sword

Has taken death as his reward.

Those who go single are galore,

Who love the sword are alone no more!

Foe for foe, ha! Head for head!

Two men by their own hands are dead.

In the palace, the king sat high on his throne. He kills people with his sword out of sheer boredom. The Man in Black enters the palace, reporting that the young boy’s head could dance gracefully in the boiling golden cauldron, offering entertainment to the king.

The boy’s head is thrown into the cauldron, but for a long time, nothing happens. Furious, the king and his ministers are ready to throw the Man in Black into the cauldron as well. But he suddenly begins to sing, and so does the boy’s head. When the song fades, the king approaches the cauldron, gazing at the head. It looks familiar. In the blink of an eye, the Man in Black raises his sword, and the king’s head was severed. Well done!

The story enters its climax from this point on: the boy’s head and the king’s head fight a frantic battle. Alas, what are they fighting for since both are already doomed? But the boy must fight to triumph over the violent spirit, ensuring it will never rise again. It’s somewhat reminiscent of Dante’s Inferno, where those who meet in life continue their battles after death, their souls locked in eternal conflict between justice and evil.

However, the boy’s powers prove unable to overcome the old villain, and his cries of defeat reach outside the cauldron. At this moment, the Man in Black, calmly embracing death, severs his own head into the boiling water. In the final showdown, the three heads fight fiercely until all three meet their ultimate demise together. An epic battle, unmatched in splendor, shaking heaven and earth, and moving gods and ghosts alike to tears! King, you never have to dream of a crystal coffin anymore!

Lu Xun’s original story taps into the spirit of resistance found in this ancient legend, creating the figure of the Man in Black and making him a symbol of wisdom and courage. “Forging the Swords” reveals the transmission of painful memories and the spirit of do-or-die resistance. The image of sacrificial head offering is also present in Western religious art, but Lu Xun’s writing carries no religious undertones. His depiction of the battle of the three heads presents a world where evil is eradicated with a vengeance, driven by a fearless, uncompromising spirit. It is tragic, heroic, and exhilarating.

As for the “Song of the Man in Black,” it begins with a slightly eerie tone, and Wang Xilin's singing is deep and subtle. Then, a more powerful and elevated energy surges in, reminding me of the famous song from Les Misérables — "Do You Hear the People Sing?" The music of Forging the Swords incorporates many folk elements, adding narrative quality to the composition and creating dramatic tension at the same time. The music is raw and intense, and the blend of the musician’s imagination with the strange sounds of folk percussion evokes the primal vitality preserved in traditional Chinese art.

Such heroic intensity can only be truly interpreted by someone like Wang Xilin whose life has been forged by so much hardship. By contrast, those popular "communist revolutionary classics" are often nothing more than a variety of sycophantic, soulless melodies.

I also listened to Wang Xilin’s “Dance of the Three Heads in the Cauldron.” Such a complex and intense piece needs to be heard repeatedly to fully comprehend it. My initial impression is that it portrays a fierce and brutal battle, an ancient legend expressed through modern music. Perhaps those familiar with Chinese literature would recall the savageness of “Forging the Swords” — the cunning, the determination, the will to battle it out till the end, and in the process, the noble and explosive force of a folk swordsman.

Ordinary Chinese audiences may not be familiar with Lu Xun's “Forging the Swords” and still less so are the international audiences. However, if one considers the intertextual connections between classic works, they might better grasp Wang Xilin’s deeper intentions. Through his work, Wang Xilin pays tribute to Lu Xun and to China’s folk tradition of rebellion. Imagine hearing those dissonant tones at the live performance and contemplating the sacrifice and suffering of generations of Chinese people. Your heart and soul would rise. Surrounded by such blood-stirring sounds, wouldn’t you start to see a possibility that, one day, the spirit of the Chinese people would arise from a deadly slumber, and a long-lost soul would begin to stir?

The purpose of Wang Xilin’s composition is to breathe life back into the spirit of a nation.

Blessings to Mr. Wang Xilin and Zhou Xiaoxia, and congratulations to Wang Bing on completing this great work!

September 6, 2023

图6 王西麟“文革”前在大同雁北文工团,摄于1964年。

二 “人的躯体是一切苦难的承受者”

——王西麟与艾晓明谈王兵纪录片《黑衣人》

作者:王西麟 艾晓明

07 王西麟在山西大同雁北文工团宿舍,1964年。

写在前面:通过王老师传来的链接,我看了王兵的纪录片《黑衣人》,并给王老师发去了我的观感:《裸体的黑衣人——灵魂的胜利》。

王老师短信中回复我:我是1971年1月被救,逃出了雁北。如果还留在雁北,结局是八成被打死,两成被逼疯。

王老师在微信里唱过他的《黑衣人歌》,即使听见了他的声音,看过他的照片,我也一直没有见过他。而在王兵的纪录片中,我终于看到了王西麟老师,却一点也不觉陌生。他已经八十六岁了,应该说是高龄老人了;但是我觉得他的灵魂正当年少,他仿佛既是《铸剑》中的那个黑衣人、又是少年眉间尺。我向王老师汇报过阅读鲁迅《铸剑》的心得,这就是以上第一篇文章的缘起。

有关这部纪录片,王老师给我一些短信回复。以下就是我的观感和王老师的回应,希望王老师宝贵的创作思考能帮助读者和观众,理解他与导演王兵的创意合作。谢谢王老师!

1 裸体的《黑衣人》——灵魂的胜利

艾晓明

图8 王西麟出席戛纳电影节,2023年5月,王颖摄。

我看过有关《黑衣人》的一些影评,在未看到影片时我曾想,为什么让王老师裸体面对观众?王老师是音乐家,如果他西装革履出场,就不能讲过去的故事吗?难道不会讲得更好吗?

因为这部作品并不能在此地上映,我是通过王老师发来的网络链接下载视频,再连接电视机观看的。电视屏幕的画幅和私人观看的方式肯定减低了作品的播放效果和感染力,但我依然感动,诚服,并且受到震撼。

王老师袒露自己的身体,这是一位八十多岁长者的身体,是一位音乐家的身体,可是他做的是什么动作啊!是躬身低头认罪,是“喷气式”,是劳动改造,超负荷强迫劳动,身体和精神不堪折磨而倒下……赤身裸体本是一个人生命的原始形态,身体,在很多时候它是被无视的;作为人,我们有精神生活,有思想追求,有艺术和人性的宽广世界,有深邃的灵魂奏鸣;但是,在那一代人中,在那漫长的毛泽东时代,所有可以称之为精神、灵魂、艺术、追求、信仰……即人之区别于动物的那些因素,人的内在而丰富的世界,全部被打碎,被否定,被践踏,被摧残……用所有的形容词不足以描述时代的凶残和荒谬。人被剥夺了一切之后,还剩下了什么呢?就是这个肉体,它在承受一切。人的生命仅余肉体,这是易受伤害的肉体,不堪一击。

我们在这个饱经风霜的肉体上,在那种种扭曲的动作里,看到了毛泽东时代知识分子的形象,他被被流放、殴打、羞辱,他们被监禁直至灭绝,我想到一个又一个中国人,从知名艺术家到底层社会的饿殍……王西麟此时潸然而下的眼泪,注定是为那么多无辜的牺牲而流淌的!

就是这样的肉体,这是被统治者认为可以任意夺取的肉体。是的,权力的意志当然可以战胜一个人的肉体,说来说去,肉体是什么东西?它有什么神圣之处?和生命的伟大可以毫无关系,可以直接碾入尘埃。

然后音乐起来了,这是王西麟的音乐,是他灵魂的迸发、精神力量的奔突。那声音的复杂、刺耳和与那个时代象征性地勾连起来,那喧哗中升腾起音乐家的灵魂的形象!是这样的赤裸的精神,但是多么不屈不挠。生命的困苦锻造了语言的力量,那个人们称之为精神的东西,那不同语言和种族的人可以共享的声响、旋律、节奏,那飞扬跋扈的爆发,它在诉说人类的悲剧!它的强悍与脆弱的身体形成对比,与权力的意志形成对比!生命会消失,然而,这音乐的创造比生命本身,比一切非人的政治力量更长久!

《黑衣人》的形象来自鲁迅《故事新编》中的《铸剑》,王兵纪录片中的王西麟老师,披挂着那个时代黑暗氛围、负载着那些血腥扑面的黑暗记忆,完成了他最重要的心血之作《铸剑》。在纪录片中,我们看到了对《铸剑》里那个精神原型的拥抱:远古的隐身志士,经过漫长的潜心准备,毅然上路,和青年交接,与帝王鏖战……在王老师的容颜里,我们看见岁月沧桑,看见了一代被噤声的知识分子,但更重要的是看见了不屈的傲骨、奔放的创造力;通过这音乐的道成肉身,我们看见了人类灵魂的胜利!

致敬王兵,致敬王西麟老师——愿您保重、强健!活过一百年!而且,即使有一天您已在天国,您的音乐创作还会在人间替您活下去!

图9 我用兰州画家陈星先生的画作设计了这个年历,请朋友带去送给王西麟先生和夫人周晓霞女士,在他们身后墙上的写有“铸剑”二字的条幅,是苏州书法家心銕的作品。2022年2月,Tianjue摄。

2 王西麟:“人的躯体是一切苦难的承受者”

——致艾晓明谈《黑衣人》

艾晓明老师,你好啊!谢谢你观看《黑衣人》影片感伤的文章!你毕竟是文学家,文字不同一般啊!

不过我要告诉你:我做的所有动作,都是我在被斗、被打、被劳改时的情景,扛沉重的大箱子……最惨烈的是被打得在地上翻滚,还有被打得在地上爬的动作,我老了都做不出了!

我唱的是我的作品《殇》,就是我曾建议你在你的纪录片《夹边沟祭事》里代替插曲《夜半歌声》之处,这在几年前我已说过了。

纪录片《黑衣人》中所用的音乐,他们选自我的《第四交响曲》《钢琴协奏曲》《黑衣人歌》《殇》,还有《小提琴协奏曲第二乐章》。王兵说:“人的躯体是一切苦难的承受者”,从他的这句话,我一下子就彻底明白了他的艺术构思的目的。我又马上意识到,“同样的,这个躯体又是艺术的创造者”,就是说影片中要选用我的音乐作品。而我也一下子就意识到,我的动作,就是我在(文革中 )被打的动作(而这是他不知道的,我就自己做出来即可)。

用裸体的意义深刻而深远啊!这是王兵作为导演极好的艺术构思!我一开始就意识到了,我全力支持他!人的生命的这个躯体被极权者践踏,但是被艺术家高度尊重!

在拍摄中,摄影师的艺术感觉特好;她一下子就知道了我的动作的意义!而且她拍出了我的身体的皱褶和老去的部位,这些画面显示了她敏锐的艺术感觉,她是天才的艺术摄影大师。

你觉得在我说话时,应该减弱背景音乐;但我的说话可以看字幕,我认为应该大大突出音乐作品的效果。在影片中开始,我在无声中走了很长时间。一进入场地时,音乐突然强烈爆发:录音师极好!影片这样使用音乐,是很有力和有效的艺术处理。这里的音乐正是“第四交响曲”开始的十分钟慢板后第一次强烈的爆发,是对巨大的浩劫来临的强烈表达。

请好好再看影片,感受音乐和画面结合的艺术设计吧!

我深深感谢导演王兵和摄影师、录音师等团队,感谢每一位艺术感觉极好的合作者!

我期望我音乐作品能被乐团和指挥发现,被广大爱乐者们发现,期望在音乐会上演奏这些作品!

图10 王西麟新作《弦乐三章》在Koblenz 首演后谢幕,2023年1月29日,周晓霞摄。

‘The Human Body Is the Bearer of All Suffering’

Wang Xilin and Ai Xiaoming discuss Wang Bing’s documentary ‘The Man in Black’

Wang Xilin (王西麟) and Ai Xiaoming (艾晓明)

Introduction

Not long ago, Mr. Wang Xilin sent me a message saying that he had finally completed his opera, Forging the Swords (《铸剑》). Over the last few years he has devoted to this work, and I’m truly happy for his accomplishment. I also watched Wang Bing's documentary The Man in Black (《黑衣人》) and shared my thoughts with Mr. Wang, The Naked Man in Black — A Triumph of the Soul.

In his reply, Mr. Wang said: “I was rescued in January 1971 and escaped from Yanbei Prefecture [in northern Shanxi Province]. If I had stayed in Yanbei, there was a good chance that I would have been beaten to death, or driven insane during the Cultural Revolution.

Mr. Wang had once sung his “Song of the Man in Black” on WeChat. Even though I have heard his voice and seen his photo, I have never actually met him in person. But in Wang Bing’s documentary, I finally saw Wang Xilin, and didn’t feel he was a stranger at all. He’s 86 in the film and he’s 88 now, yet I feel his soul is as young as ever. He is both the Man in Black from Forging the Swords as well as the young hero Mei Jian Chi (眉间尺) from the same story. I had shared my thoughts with Mr. Wang about reading Lu Xun’s original short story “Forging the Sword,” but that is a discussion for another article.

Regarding the documentary, Mr. Wang has texted responses, which I’ve organized below. I believe these valuable insights into his creative process will help readers and viewers better understand the collaboration between Wang Xilin and director Wang Bing.

Ai Xiaoming

The Naked "Man in Black" — The Triumph of the Soul

Ai Xiaoming

I had read some reviews of The Man in Black before seeing the film, and I wondered: Why did they have Mr. Wang appear naked before the audience? He is a musician. If he had appeared dressed in a suit, wouldn’t he still be able to tell his story just the same? Perhaps he could have even told it better.

Since the film is not available for screening in China, I downloaded it through a video link Mr. Wang sent me, then connected it to my TV to watch. Watching it on a TV screen in private certainly lessened the impact and emotional power of the film, but I was still moved, humbled, and deeply shaken.

Mr. Wang bares his body — the body of a man in his eighties, the body of a musician. He bows his head in repentance, mimicking the "jet-plane posture" used in the laogai camps, simulating overwork and collapse under physical and mental torment.

Being naked is the original state of human life, yet the body is often ignored. As humans, we have a spiritual life, intellectual pursuits, and a vast world of art and humanity. We host within ourselves profound spiritual symphonies. But for that generation, during the long rule of Mao Zedong, everything that could be called spirit, soul, art, pursuit, belief — everything that distinguishes humans from animals—was shattered, denied, trampled, and destroyed. No adjectives are sufficient to describe the cruelty and absurdity of that time. After everything is taken from a person, what remains? Only the body. The body alone bears everything, the vulnerable and fragile body human life is reduced to.

On this weathered body and through these distorted gestures, we see the image of intellectuals during the Mao era — exiled, beaten, humiliated, imprisoned to the point of destruction. I think of one Chinese person after another, from renowned artists to the starving dead at the bottom of the society. The tears Mr. Wang sheds are for the countless innocent lives lost.

This is the body that the rulers believe they could take at will. Yes, the power of the rulers can certainly triumph over a man’s. After all, what is flesh? What is sacred about it? It can be ground into dust without a thought for its greatness.

Then and there the music rises — Wang Xilin’s music, an outburst of soul, a surge of spiritual power. The complexity and harshness of the sound connects symbolically with that era, and amid the ding, the image of the musician’s soul ascends! It is a naked spirit, and indomitable! The hardship of life forges the power of language. Together, that intangible thing called spirit, the sounds, the melodies, and the rhythms that transcend language and race, the defiant outbursts that tell the tragedy of humanity! What a sharp contrast between the frailty of the body and the will of the powerful! Life may be extinguished, but the musical creation endures beyond life itself, outlasting all inhuman political forces!

The figure of the Man in Black comes from Lu Xun's “Forging the Swords” in his collection Old Tales Retold. In Wang Bing’s documentary, we see Mr. Wang Xilin draped in the darkness of that era, burdened with the bloody memories of its oppressive atmosphere, completing his greatest work, Forging the Swords. In the documentary, we witness an embrace of the spiritual archetype in Lu Xun’s original work: the ancient hidden warrior, after long preparation, sets off decisively to meet the young, to battle with the ruler. Etched in Mr. Wang’s face we see the toll of time and the silence imposed on a generation of intellectuals. But more importantly, we see unyielding pride and boundless creativity. Through the incarnation of music, we witness the triumph of the human soul!

A salute to Wang Bing and Mr. Wang Xilin — may you stay healthy and strong! Live beyond a hundred years! And even if one day you are in heaven, your musical legacy will live on in this world!

Wang Xilin: ‘The Human Body Is the Bearer of All Suffering’

— To Ai Xiaoming on The Man in Black

Hello, Ms. Ai Xiaoming! Thank you for your moving article after watching The Man in Black! You are truly a writer; your words are exceptional!

However, I must tell you: All the movements I made in the film are scenes from when I was being struggled against, beaten, and forced into labor. Carrying heavy crates... The most tragic scene was when I was savagely beaten, rolling on the ground, and crawling on the ground. I’m too old now to fully recreate those movements!

What I sang was from my work Elegy (《殇》), which I once suggested that you use in your documentary The Jiabiangou Elegy (《夹边沟祭事》) to replace the Song at Midnight (《夜半歌声》) — I mentioned this a few years ago.

The music used in The Man in Black documentary includes selections from my Fourth Symphony, Piano Concerto, Song of the Man in Black, Elegy, and the second movement of my Violin Concerto. Wang Bing said: "The human body is the bearer of all suffering." From that utterance of his, I immediately understood the purpose of his artistic concept. Then, I quickly realized, "Likewise, this body is also the creator of art," which is to say that, in addition to presenting my music in the film, my body would have to be there too, simulating the movements when I was beaten during the Cultural Revolution, which Wang Bing left it to myself, not knowing how I would perform.

The profound meaning of using nudity cannot be overstated. Here Wang Bing shows his creativity as the director. I understood and fully supported the idea from the very beginning. This human body, once trampled underfoot by tyrants, is being held in high regard by artists.

The cinematographer displayed an exceptional artistic sense during the filming. She immediately grasped the meaning of my movements. Moreover, she captured the folds of my aging body. These images reflect her sharp artistic instincts — she is a brilliant, genius cinematographer.

You suggested that the background music be lowered when I speak, but subtitles can accompany my words. I believe that the musical effect should be greatly emphasized. At the beginning of the film, I walk in silence for a long time. When I enter the space, the music suddenly erupts with intensity. The sound engineer did an excellent job! The way music is used in the film is powerful and effective as an artistic treatment. It is the first explosion of music following the ten-minute adagio of the start of my Fourth Symphony, indicating the befalling of an overwhelming catastrophe.

Please watch the film again and take in the artistic design that combines the music and the visuals.

I am deeply grateful to director Wang Bing, to the cinematographer, the sound engineer, and the rest of the team, as well as to each and every collaborator whose keen artistic sensibility contributed to the making of the film.

I hope my musical works will be discovered by orchestras and conductors, and through them, by music lovers everywhere. I look forward to seeing these works being performed in concert halls.

图11 王西麟在戛纳电影节 2023年5月 王颖摄

歌剧《铸剑》作者的话

王西麟

在我的童少年时代,大约九岁或十岁左右,常常听我的哥哥给我讲故事。他比我大六岁,我记得他讲过屈原和楚怀王,讲过项羽、刘邦和鸿门宴的故事……记忆中印象最深的是荆轲刺秦王。

最早听到的这些故事,在我以后的记忆中,随着知识和阅历的增长,得到丰富而加深。由此建立起来的是非观、世界观,经历了漫长岁月的冲刷,几乎没有改变,那就是同情失败的弱者,谴责帝王的强权。“风潇潇兮易水寒,壮士一去兮不复还”,这义无反顾的悲歌,不但令我印象深刻,而且很多年来,常在我心中萦绕。我久久地想象那远古的历史场景,试图还原这歌声的音调和旋律的样式,我想象着,深秋时节,在已经冰封的易水河面,这歌声追魂夺魄,飘荡不散。

1993年,我应邀为导演张华勋影片《铸剑》(出品/监制徐克)作曲。哈,这就是表达我创作冲动的最佳出口!我兴奋地到达了影片拍摄的外景地——山东淄博。

导演要求我提前作好主题歌《黑衣人歌》和《祭鹰之舞》。那时,我的作品《第三交响曲》刚刚首演,我的美学观念有了飞跃;这次创作是又一个挑战!

同时,我开始研究美国现代作曲家George Crumb的《远古童声》(Ancient Voices of Children),还有来北京演出的日本音乐集团三木稔先生的一些作品,我又看了日本的 “能”剧,而最重要的灵感来自山西地方戏剧。

文革后期,我在山西上党地区度过七年岁月。我由衷地喜爱上党梆子,从深入学习到亲自投入大型戏曲《红灯照》的创作,我力求复活这一古老剧种的艺术传统。这段时期的研究和创作,这也是我在山西十四年最有意义的音乐收获。

(*补充说明:《红灯照》这个剧本歌颂义和团,这是有问题的,后来已经不演了。但是在1977年,我为这部戏担任指挥时,为地区重新恢复了在文革中被样板戏破坏了的上党梆子的古老传统,而深为当地称道。

因为文革中全国戏曲都要学演样板戏,但是全国很多地方戏曲都没有样板戏的一些板式,且方言不同。为了学习样板戏的一招一式,只能死搬硬套,这对地方戏反而是极大的破坏。演员不愿演,观众不愿看,如此十年之久。

文革结束后的1977年,上党梆子剧团的这一代青年演员正是十八九岁的年纪,她/他们虽都是戏剧世家出生,但并不知道这一剧种里老艺人所擅长的传统唱腔。我正好主持这次工作,于是我和上党梆子传统唱腔设计的好友马天云一起,我们精心挑选每段唱腔,逐段加工整理,研究乐队配器。我的指导思想就是,一定要尽可能地恢复上党梆子丰富的音乐传统。)

1993年12月的一个夜晚,在北影录音棚里,我完成了《黑衣人歌》和《三头釜中舞》的创作和录音。我当时想到,为眉间尺复仇的“黑衣人”不就是伟大的勇士荆轲吗?在录音棚里,哪里能找到这样特殊的歌者?于是我决定,我自己来唱!《黑衣人歌》就这样问世了。

《黑衣人歌》和《三头釜中舞》这两首电影歌曲,各自仅仅四分钟,三十年来成为我最著名的代表作。在美国、欧州和港台地区多次文化交流活动中,两首作品引起强烈反响。2022年,著名的优秀导演王兵先生在法国为我拍摄了纪录片,也用了《黑衣人》为影片命名。

从1993年为电影《铸剑》作曲开始,我就想把这个故事作成歌剧,迄今已整整三十年了。《黑衣人》就是我自少年时代起就神往不已的荆轲啊,他为正义和公正而慷慨赴死,这种义勇就是歌剧的灵魂。《黑衣人歌》塑造的音乐形象,应该是中国音乐史上一个伟大的悲剧英雄。

2008年我开始构思这部歌剧,剧本初稿由我的女儿王颖执笔完成,她最大的创意是,把鲁迅小说中结尾的三头共葬,改为王宫的倒塌。这个改变,极大地深化了歌剧的主题和立意。

而真正启动这部歌剧的音乐创作,还是在六年以前。2018年,我来到德国生活,这时我才有了可能去歌剧院听歌剧,观看演出的现场。与此同时,我开始写作,很快完成了第一幕和第二幕。我为这部三幕歌剧呕心沥血,如今已是2023年的尽头,我的计划终于全部完成,这是我平生创作的第一部歌剧。

在写作中,我有意采用了小说原作中的大量对话;以此向鲁迅先生致敬。

我把这部歌剧献给——

我的哥哥王庆麟,1961年他在甘肃兰州饿死,年仅三十一岁;

我的启蒙老师、甘肃平凉晨光小学校长田仲章先生;在我的少年时代,他为我奠定了成长的基础。1949后他在甘肃省文化局工作,1957被打成右派。1962我从上海音乐学院毕业,他竟亲自来上海看我。“文革”结束后我马上找他,却不料他已死于车祸!

我没法报答他们的伟大恩情,我把这部歌剧题献给他们。

Comments From the Creator of the Opera ‘Forging the Swords’

Wang Xilin

During my childhood, around the age of nine or ten, I often listened to my brother, six years my senior, telling stories. I remember the stories of poets, warriors, and emperors, such as that of Qu Yuan and King Huai of Chu, about Xiang Yu, Liu Bang, and the Banquet at Hongmen... But the one that left the deepest impression on me was Jing Ke's attempt to assassinate the King of Qin.

These childhood stories have deepened and become more vivid in my memory as my knowledge and life experience have grown. From them I formed my sense of right and wrong, my worldview. Over the long course of time, they have remained largely unchanged, and that is, to sympathize with the weak and downtrodden, and to condemn the tyranny of despots. The melancholic verse — "the wind howling, the Yi River frozen, the hero is gone, never to return" — that Jing Ke sang as he departed for the Qin court left a lasting impression on me and has haunted my mind for many years. I often imagined those ancient scenes, trying to recreate the tones and melodies of that sorrowful song. In my mind, I pictured a late autumn scene, with the song echoing throughout the chilled air over the frozen waters of the Yi.

In 1993, I was invited to compose the music for director Zhang Huaxun's film Forging the Swords (《铸剑》, produced by Tsui Hark. Ah, this was the perfect outlet to express my creative impulse! I was excited as I arrived at the film's shooting location in Zibo, Shandong.

The director requested that I compose the theme songs “Song of the Man in Black” (《黑衣人歌》) and “Dance of the Eagle Sacrifice” (《祭鹰之舞》) ahead of time. At that time, my Third Symphony had just premiered, and my aesthetic ideas had undergone a major leap; this new project was another challenge! At the same time, I began studying the work “Ancient Voices of Children” by modern American composer George Crumb, as well as several pieces by Japanese composer Miki Minoru, whose music group had performed in Beijing. I also watched Japanese Noh theater, but the most important inspiration came from the local theatrical traditions in Shanxi Province.

During the later years of the Cultural Revolution, I spent seven years in the Shangdang region in southeastern Shanxi province. I developed a deep love for the traditional Shangdang opera. I immersed myself in learning and later participating in the creation of the large-scale opera The Red Lanterns (《红灯照》), I strove to revive the artistic traditions of this ancient genre. This period of research and creative work became my most significant musical achievement during the fourteen years I spent in Shanxi.

On a December night in 1993, in a recording room at the Beijing Film Studio, I completed the composition and recording of “Song of the Man in Black” and “Dance of the Three Heads in the Cauldron” (《三头釜中舞》). At that time, I thought, isn't the "Man in Black" avenging Mei Jian Chi essentially the great warrior Jing Ke? Where am I supposed to find a unique singer to sing it in the recording studio? So, I decided to sing it myself ! And that’s how “Song of the Man in Black” was born.

Both “Song of the Man in Black” and “Dance of the Three Heads in the Cauldron” are only four minutes each, but over the past thirty years, they have become two of my most representative works. During numerous cultural exchange events in the United States, Europe, and Hong Kong and Taiwan, these two pieces sparked strong reactions. In 2022, the renowned and talented director Wang Bing (王兵) filmed a documentary about me in France, going so far as to title it The Man in Black (《黑衣人》).

Ever since I wrote the two songs for the film Forging the Swords in 1993, I’ve wanted to turn this story into an opera. It has now been exactly thirty years. The Man in Black is the Jing Ke I’ve admired since my youth, who heroically sacrificed himself for justice and righteousness. This kind of bravery is the soul of opera. The musical image created by Song of the Man in Black should stand as a great tragic hero in the history of Chinese music.

I began to conceive the opera in 2008. My daughter Wang Ying wrote the first draft of the script. Her most significant idea was changing the ending from the triple heads burial in Lu Xun's original story to the collapse of the palace. This change greatly deepened the theme and meaning of the opera.

The actual musical composition didn’t begin until six years ago. In 2018, I moved to live in Germany, where I finally had the opportunity to attend operas and watch live performances at theaters. At the same time, I started writing, quickly completing the first and second acts. I poured my heart and soul into this three-act opera. Now, at the end of 2023, I have finally completed the entire work as planned. This is the first opera I have created in my life.

During the writing process, I deliberately incorporated a large amount of dialogue from the original work as a tribute to Mr. Lu Xun.

I dedicate this opera to:

My brother, Wang Qinglin (王庆麟), who died of starvation in Lanzhou, Gansu Province, in 1961, at the age of 31.

My childhood teacher Mr. Tian Zhongzhang (田仲章) who was the principal of Chenguang Elementary School in Pingliang, Gansu Province. He laid the foundation for my growth during my boyhood. After 1949, he worked at the Gansu Provincial Department of Culture, but in 1957, he was labeled a "rightist." In 1962, after I graduated from the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, he came all the way to Shanghai to see me. After the Cultural Revolution ended, I immediately sought him out, only to learn that he had died in a car accident.

I have no way to repay the immense kindness these two individuals have shown me. To them I dedicate this opera.

Translated by Leo Timm

2024年9月30日编定。