Shuishan Yu:Understanding The Holiest Sites On Earth

本文為《波士頓書評》2024-01期文章,本期刊物電子版下載。

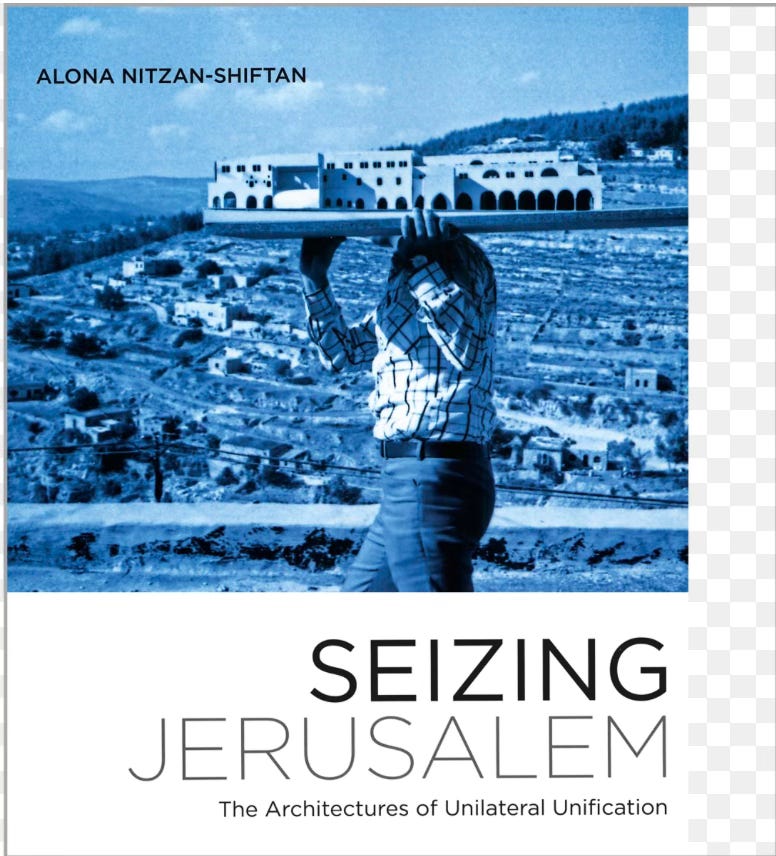

Alona Nitzan-Shiftan, Seizing Jerusalem: The Architectures of Unilateral Unification, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Alona Nitzan-Shiftan’s 2017 book Seizing Jerusalem: The Architectures of Unilateral Unification can be of great interest to architectural professionals, cultural scholars, social political critics, international affair observers, and public readers in general. The author is a professor of architecture at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa who belongs to the generation of Israelites growing up during the momentous years after the war in 1967, a period her writing covers. The book features detailed accounts on some key architectural and planning projects from the 1950s to the 1970s in and around the Holy City of Jerusalem, tracing the changing cultural policies of the state and establishing an interconnected relationship between architecture and politics in one of the world’s most contested and violent sites.

In the political study of architectural history, scholars have been rendering architects either as innocent and eventually pressured for submission to politics or as acquiescent collaborators. Nitzan-Shiftan tried to go beyond such depictions, which she considered both depoliticized architectural practices. Instead, the author proposed “architecture” as a verb, “a spatial form of action, a mode of operating and politicizing space.” Following the introduction that prepares the theoretical and historical background, six following chapters gradually zoom in to the re-design project of the sacred heart of Jerusalem, the Western Wall, popularly known as the Wailing Wall. Chapter 1 furthers the theoretical and historical discussions on the relationship between modern architecture and the Israeli nationalism. Chapter 2 and 3 offer deep analyses of the major participants and organizations for the architectural transformation of Jerusalem, the sabra (Israeli born) architects, the Ministry of Housing, etc, and the various housing projects on controversial lands. Chapter 4 concentrates on the urban beautification movement under the leadership of the major’s office. Chapter 5 puts the reshaping of the Old City in East Jerusalem within an international stage and against a broader disciplinary backdrop. Finally, Chapter 6 chronicles the process and proposals for the project of the Western Wall Plaza, the spiritual home for the Hebrew world within and without Israel.

This book offers great details on the design and formation of the built environments in Jerusalem, in which much of the current tragic dramas are going on. It gives readers deeper understanding on both architecture, history, and politics. The sources of the author include recently released archival documents and years of interviews with government officials and architectural professionals. The book provides much needed insights on how and why one of the holiest sites on earth has come to its current forms, and maybe the happenings contained in its spaces as well.

A good book often goes beyond the scholarly details of a specified location or discipline. Nitzan-Shiftan’s Seizing Jerusalem does this on different levels and aspects. In the field of architectural history, the author sets the pre and post 1967 Israeli architecture against the international transition from modern to postmodern, which she terms “developmental modernism” of the 1950s-60s vs. the “situated modernism” after the 1970s. In the discussion of the Jerusalem Committee founded in 1970 and various projects associated with it, for instance, the author enriches our understanding of works by such world famous architects as Buckminster Fuller, Philip Johnson, Louis Kahn, Bruno Zevi, and Moshe Safdie. In terms of social political history, the author defines a paralleled movements of the architectural vs. political modernism and delineated a convincing mutual-containing relationship between the two.

An interesting concept raised in this book is the self-conscious Orientalism by the Israeli authorities. One of the 1968 planning principles for the unified Jerusalem is to incorporate in new architecture “elements of Oriental building such as arches, domes, etc.” and “to bestow on these neighborhoods an image that accords with the landscape and character of Jerusalem” for the construction of “a national park for a world city.” According to Nitzan-Shiftan, such architectural details were found in the local Palestinian villages and transformed into a key feature of Mediterranean regionalism through new archaeological discoveries. This is another frontier where much intellectual debates can excise.

Shuishan Yu:Associate Professor of Architecture, Northeastern University