Interview | Geremie R. Barmé: Constructing “New Sinology” with an Eye to the Eastern Bloc

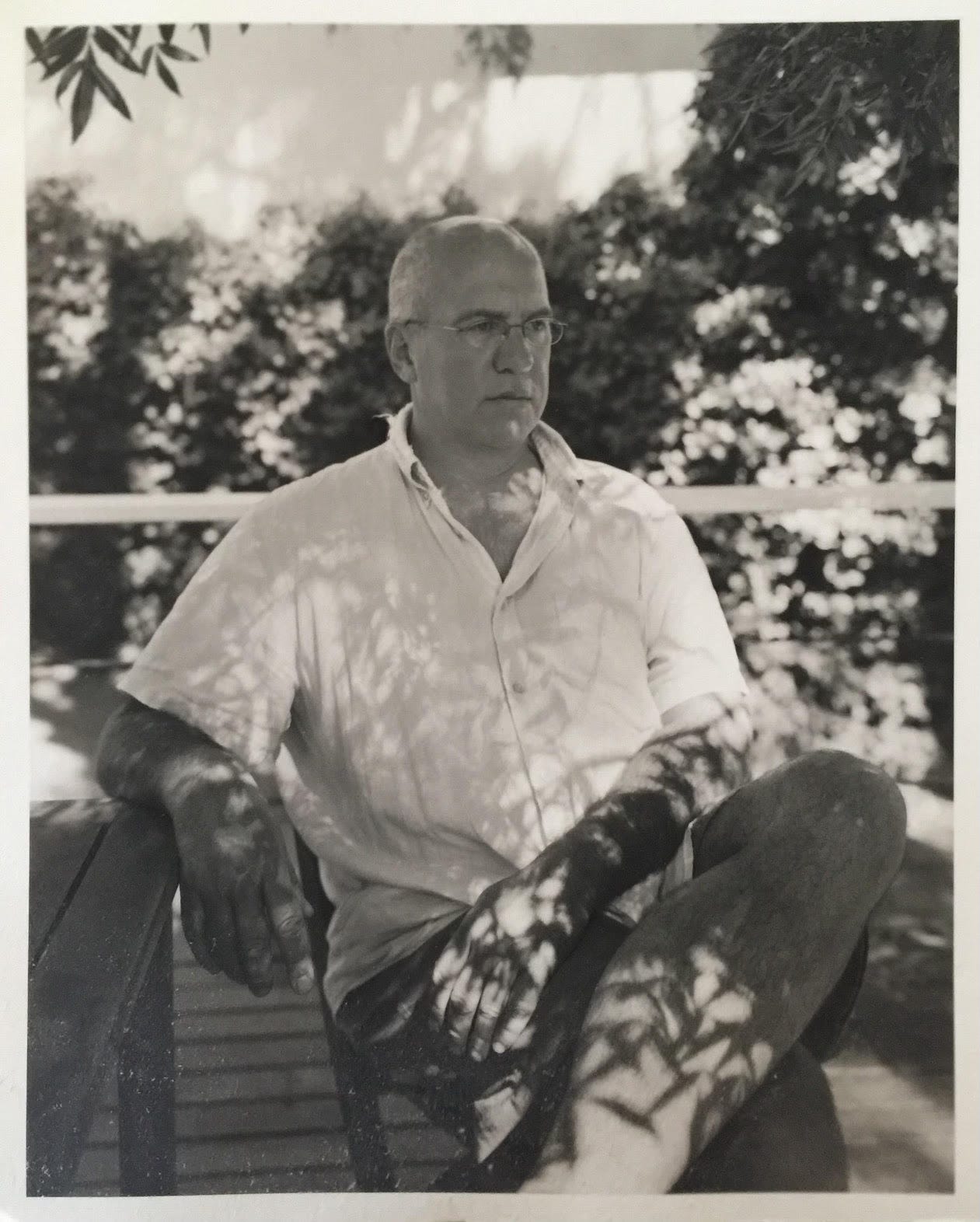

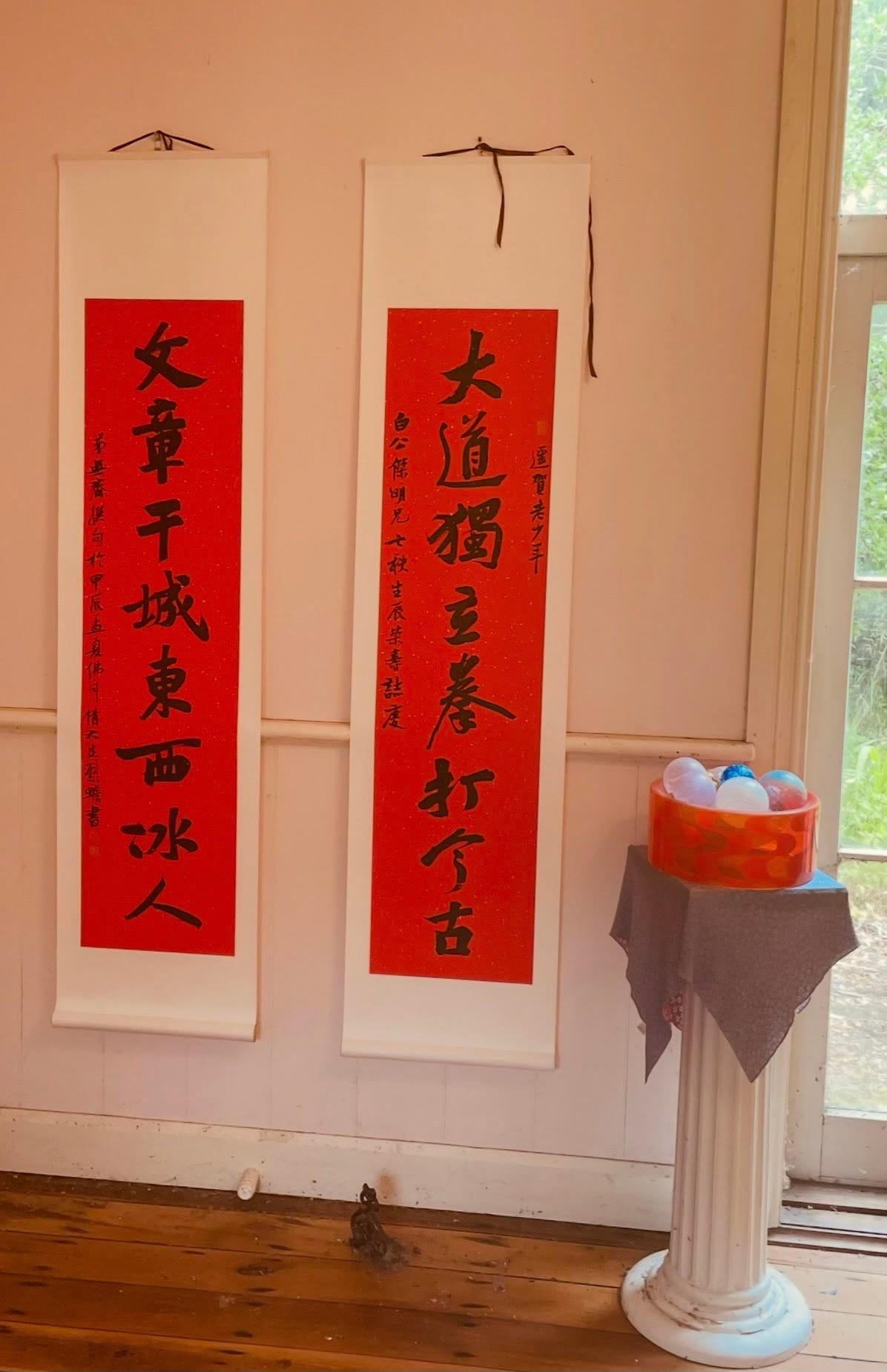

Editor’s Note: In 2005, Australian Sinologist Geremie R. Barmé proposed the concept of “New Sinology” (後漢學), which not only responds to the 1964 debate among overseas Sinologists on “Sinology vs. the Disciplines,” but also serves as the core of his scholarship. From then on, he has consciously constructed “New Sinology” through a series of practices informed with an eye to Eastern European/Soviet dissidents. What is “New Sinology”? What significance does it hold for current China studies and the contemporary world? The Boston Review of Books recently interviewed Professor Geremie R. Barmé via email.

In 1964, a notable debate known as “Sinology vs. the Disciplines” erupted in the Western community of China academics. The controversy unfolded at the annual meeting of the Association for Asian Studies and in the pages of the Journal of Asian Studies, focusing on whether the study of China should adopt the holistic approach of traditional Sinology or integrate the analytical frameworks of modern disciplines (such as history and social sciences).

Joseph R. Levenson, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, opposed traditional Sinology, arguing that its language- and text-centered methods were inadequate for addressing the needs of modern academic disciplines or for responding to the complexities of contemporary China. G. William Skinner of Stanford University even declared that “Sinology is dead” and promoted a thematic approach to Chinese Studies. In contrast, Frederick W. Mote of Princeton University, someone who had completed a degree at Nanking University in the late 1940s, defended the integrity of Sinology, emphasizing its unique value in encompassing the entirety of Chinese civilization, past and present. While Benjamin I. Schwartz of Harvard University, who criticized the new and narrow obsession with disciplinary approaches, advocated for a Sinology that embraced broader humanistic concerns. From then on, although “disciplines” would dominate institutional academics, the debate over the merits of “Sinology” versus “Chinese Studies” has never fully subsided. In 2005, Australian Sinologist and historian Geremie R. Barmé proposed the concept of *New Sinology*, which, to some extent, responded to this old debate within the context of rising China while also establishing a paradigm for New Sinology through his half-century of academic work.

In the field of international Sinology and Chinese Studies, Sinologist Barmé is not only distinctive but also often regarded by Chinese readers as one of the overseas China scholars who best understands China. His advocacy of “New Sinology” emphasizes the role of language and cultural ecology, it employs an interdisciplinary approach that spans history, art, politics, and cultural critique, integrating academic research with public discourse in the study of China. This approach has been praised by another prominent Sinologist, John Minford (閔福德), a celebrated literary translator and emeritus professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, as well as by the intellectual historian Gloria Davies (黃樂嫣) for injecting new vitality into Sinology, while expanding the scope of contemporary “China Studies” and serving as a model for bridging the classical and the modern, the traditional and the contemporary. Another notable characteristic of Geremie R. Barmé’s academic works is that, since the 1980s, Barmé has also employed the ideas of Eastern European and Soviet dissident intellectuals to help study and analyze China’s independent intellectuals and Chinese society, an approach that offers a profound exploration of the complexities of modern and contemporary Chinese culture and politics, and one that reveals the struggles and resistance of Chinese intellectuals in a changing authoritarian environment. He specifically notes that he thinks in terms of the Soviet Bloc, or the Eastern Bloc. In terms of the circulation of ideas, activism and resistance, the term “Eastern European”, though a handy tag, actually occludes reality and tends to distort the history of the time as it fails to encompass the Soviet overculture. This emphasis suggests that he values not only ideas but also practice, and the multi-perspective, comprehensive research approach emphasized by “New Sinology”.

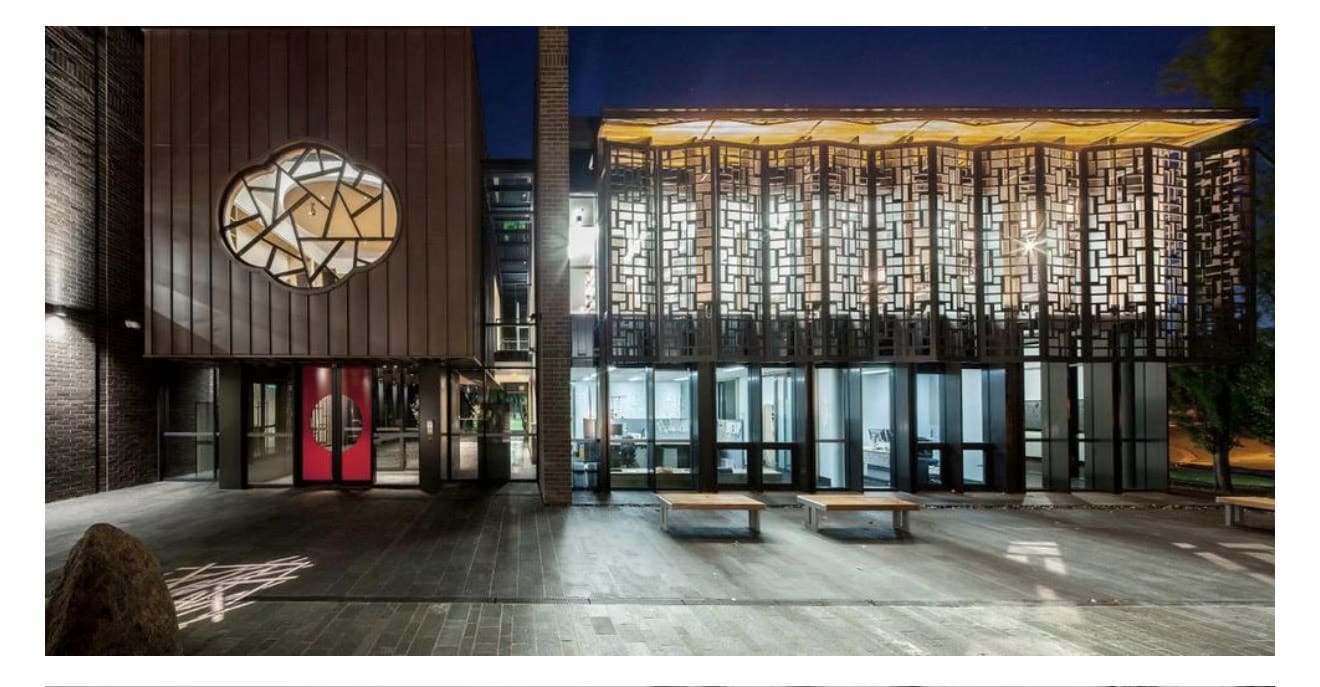

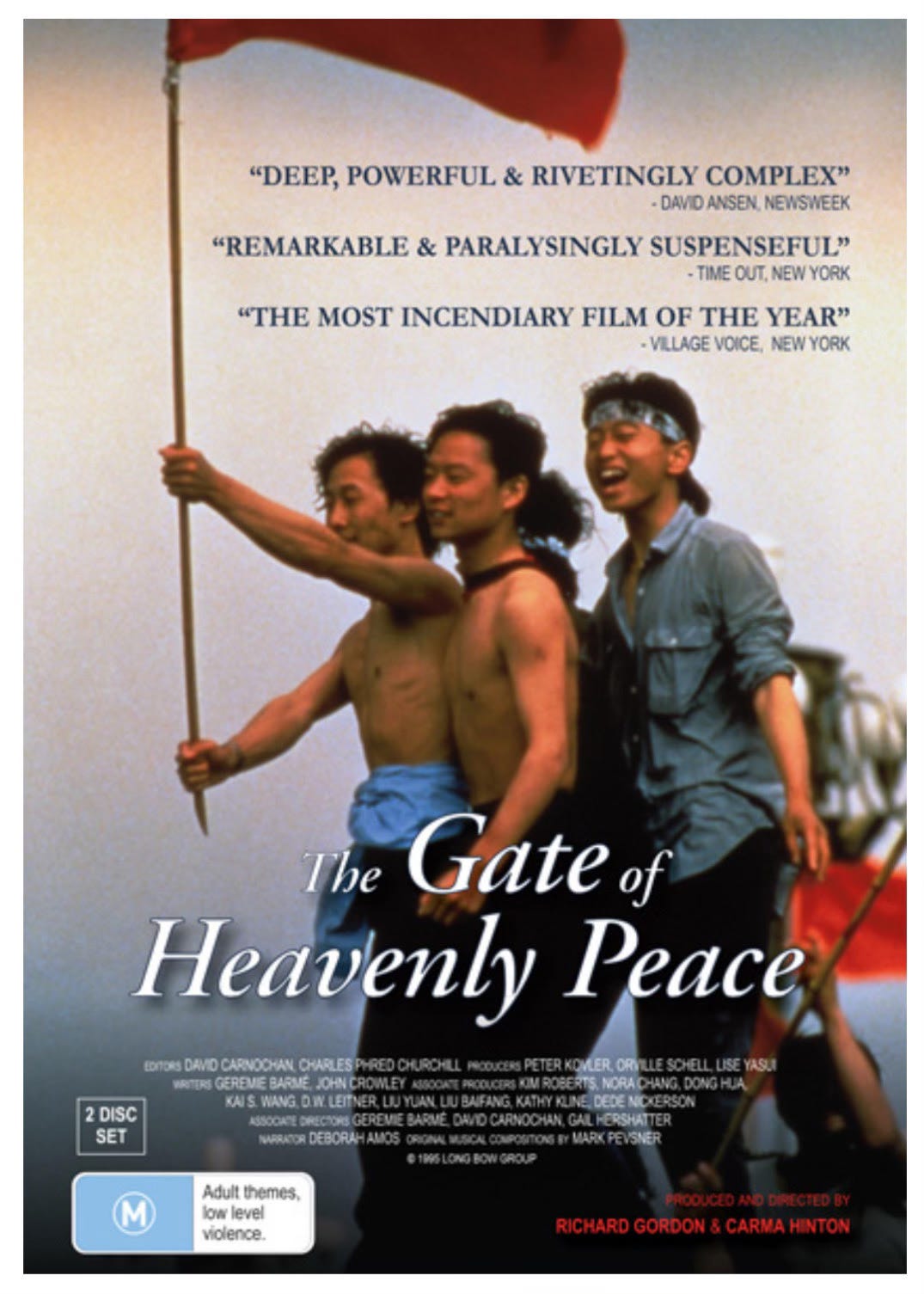

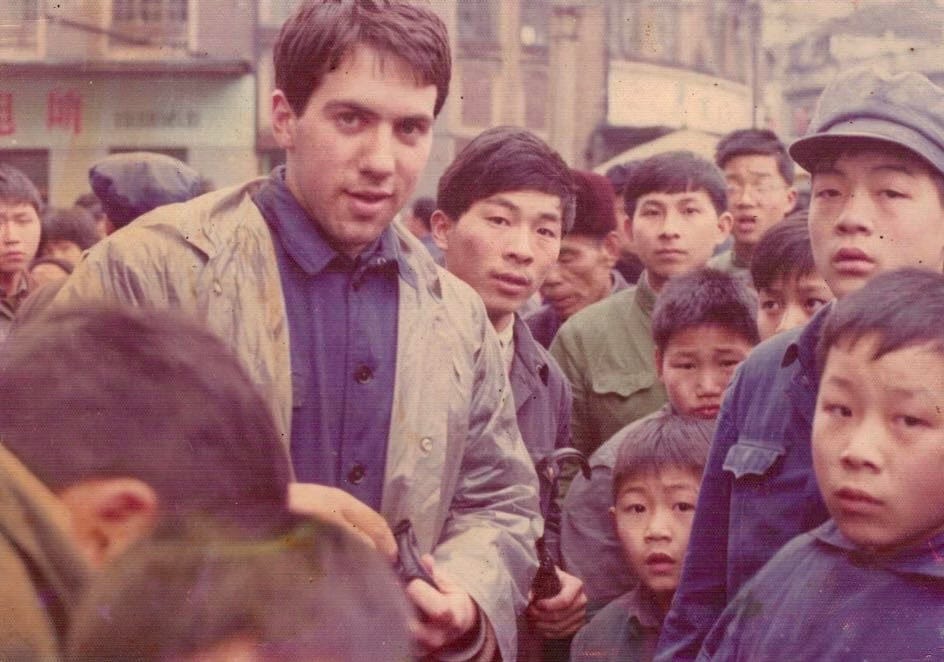

Barmé enrolled at The Australian National University (ANU) in 1972 to study Sanskrit, Chinese (classical and modern), and history, and he first traveled to China in 1974 as an exchange student, where he studied in Beijing, at Fudan University in Shanghai and at Liaoning University in Shenyang. From 1977 to the early 1980s, he worked as an editor and translator in Hong Kong, where he also began writing essays in Chinese (continuing until 1991). In the early 1980s, he also studied at universities in Japan. Upon returning to Australia, he pursued a doctorate under his mentor Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys) while continuing to write and translate. Upon graduation in 1989, he took up a postdoctoral fellowship at ANU, eventually becoming a full-time research professor, PhD supervisor, editor and centre director, roles in which he continued until he took early retirement in 2015 following a period of illness. During that time, Barmé combined his academic work in Australia with documentary film-making with the Long Bow Group in Boston. He was the lead academic adviser and main script writer for The Gate of Heavenly Peace (1995) and co-director, producer and writer of Morning Sun (2003). He also co-designed the websites for both films. In 2010, with the support of Kevin Rudd, then Australia’s Chinese-speaking prime minister who at Barmé’s suggestion had spoken about being China’s “zhengyou” 諍友 in 2008 (see Contentious Friendship), Barmé established the Australian Centre on China in the World, a multidisciplinary research institution based on the principles of New Sinology. He was director of the centre until 2015. He has described that venture in the following way:

“Recognising a new globalised era of China both as a burgeoning economic power and a potentially powerful cultural presence on the world stage, New Sinology proposed a holistic engagement with the Chinese world of ideas, politics and humanities. I summed up the ethos of my new centre as being an academic enterprise that was ‘grounded in the humanities, embraced the social sciences and engaged both with public policy and the public’. This wordy mantra was put into practice with the collaboration of a team of scholars drawn from a number of leading academic institutions who developed research topics, offered generous support for post-doctoral fellows, short courses on China for government agencies and, from 2012, a doctoral program.” (See Misplaced Faith in the Social Sciences & the Abiding Lessons of New Sinology.)

Previously, as part of the New Sinology project, Barmé founded China Heritage Quarterly (2005–2012), and the new center saw the creation of The China Story (which he edited from 2012 to 2016), this was followed by China Heritage (2016 ongoing), all online journals. During his years at ANU, Barmé was also the editor of East Asian History from 1991 to 2006 as well as being the main editor of the first three volumes in The China Story Yearbook series, which he founded in 2012 (see Red Rising, Red Eclipse, Civilising China and Shared Destiny).

Since the 1970s, Geremie R. Barmé’s academic career, spanning over half a century, has been marked by two distinct characteristics: first, the research methodology of New Sinology; second, the embedded perspective of Soviet and Eastern European dissidents. In his view, even his books An Artistic Exile: a life of Feng Zikai (1898-1975), published in 2002 and The Forbidden City (2008) also reflect this approach.

What is “New Sinology”? How does one view China through the lens of the Eastern Bloc? The Boston Review of Books interviewed Professor Geremie R. Barmé via email.

Q: I once asked you why you translate the term “New Sinology” as “後漢學” (“Post-Sinology”) instead, for example, as “新漢學” (literally, “New Sinology”)? What does “後” (Post-) mean in this context?

A:I chose 後漢學 as the translation for New Sinology for a number of reasons. In the first place 漢學 was, from the time of the interactions between European missionaries and Chinese literati in the late-Ming dynasty a term used to refer to that body of canonical texts seen as having been codified in the Han dynasty and subsequently employed as the measure of knowledge, culture and political thought, and the basis for rulership, in particular from the Song era. Today, most people, be they Chinese or even Western academics, fail to appreciate this lineage and there is a tendency, in particular in the Anglophone world, to be dismissive of Sinology as merely irrelevant arcana and dusty philology. In reality, from its origins “Sinology” 漢學 was about studying the key texts, ideas and culture of the literate Chinese world. From the start it was a form of engaged scholarship that involved understanding China as part of an enterprise to infiltrate and even transform it. In the early Republic, the old Ming term for the corpus of traditional learning, arts and statecraft was recast as 國學 “National Studies” (see Sinology vs. the Disciplines, Then & Now).

As for the fate of “Sinology” in the West, as I just noted, readers should be aware that the academic pursuit of Sinology has been seen very differently in Europe and Japan compared to America and the Anglosphere more generally (that is the realm of Anglo-American intellectual hegemony and “industrial-scale knowledge production”). In 1964, as you note in your editor’s introduction, there was an important debate on Sinology and the Disciplines to which readers might like to refer (again, see New Sinology in 1964 and 2022).

From its inception, New Sinology has had its critics, be they academic or journalistic. Although, in most cases, the criticisms have said more about the intellectual narrowness and rank ignorance of their authors than the limitations of my proposal (see, for instance, my comments on a celebrated American undercover journalist in The Good Caucasian of Sichuan & Kumbaya China). For such critics who believe they really “get” China and “the Chinese”, New Sinology is synonymous with the obscure, bookish and out-of-touch.

In my younger years, I was rather enamoured by the intellectual and verbal pyrotechnics of Joseph Levenson, who was an outspoken participant in the 1964 debate, and I was sympathetic to his view of post-1949 “Maoist” China as having at best constructed a “museum” of the past. Over the years, however, as I learned, read and travelled more, I came to side rather with Ben Schwartz, another great intellectual historian and commentator in the ’64 debate, who said that:

“…one has questions concerning Levenson’s metaphor of the museum. The artifacts in a museum can be appreciated, as Levenson would heartily concede, for their present aesthetic value. On the technological side, one can take pride in the technological accomplishments of our predecessors … . The nonmaterial side of culture is, it seems to me, not so easily dealt with in terms of this metaphor. I would suggest that a library may furnish a more apt metaphor. Those who write books more often than not ardently hope that putting their books in libraries will not necessarily assure the deadness of their ideas. Vast numbers of volumes may indeed go unread ever after, but one can never guarantee that they will remain mute.” (See Benjamin I. Schwartz, History and Culture in the Thought of Joseph Levenson, 1976).

I would argue that, since the death of Mao, the metaphor of the library rather than that of the museum has been more useful in appreciating the complex rebirth, revival and reconfiguration of the Chinese world, a process that the Communists refer to in terms of “creative adaptation” 創造性的轉化, or, since 2023, by using more nebulous expressions such as 魂脈 and 根脈. Generally speaking, some of these formulations, sans the vacuous Party palaver, chime with my advocacy of New Sinology.

As for the 後 “post” in 後漢學, let me explain: in the first place, I used the Chinese term 後漢學 for New Sinology to acknowledge the lineage between the efforts of scholars over the centuries to come to grips with the complex body of Chinese texts, ideas, modalities of rulership, culture and social realities that were the concern of Sinology and generations of Sinologists.

Secondly, by using 後漢, in the meaning of “Latter Han”, I was making a case for the connection between my interests in China in the twenty first century, and the equitable approach to that Sinophone world that I advocated, and the relationship between those first western Sinologues and the powerful Ming empire in the early 16th century. 後漢 has encoded within it both a serious historical dimension and a somewhat light-hearted approach that reflects my personal demeanour in regard to the study of the Chinese world (people can be so tediously serious!).

On top of that, 後學 itself is a common term that younger scholars use when referring to their intellectual masters and predecessors. It is also a reference to Dong Zhongshu 董仲舒, the Han-dynasty master, who is spoken of in the following way:

仲舒遭漢承秦滅學之後,六經離析,下帷發憤,潛心大業,令後學者有所統壹,為羣儒首。

The key line being: 後學者有所統壹. But, in saying this, I would emphasis that I am no advocate of the “Great Unity” or State Confucianism, be it of the dynastic past or in the present of the Chinese party-state. Quite the opposite.

Thirdly, the use of 後 — “latter”, “later” or “post” — is also a tongue-in-cheek reference to the 1990s Mainland Chinese intellectual fashion for “post-studies” 後學, that is the garrulous amalgam of western-inspired and mostly theory driven approaches in the Chinese academy that flourished as the so-called “New Left” and the so-called “Liberals” became embroiled in performative intellectual warfare. This is a topic about which I wrote extensively in the late 1990s. See, for example, The Revolution of Resistance.

I would also note that in 2012, Hanban 漢辦 in Beijing, the headquarters of the global Confucius Institute network, announced a “New Sinology Plan”, or 新漢學計劃 in Chinese. A speaker at the Forum for Young Sinologists and the Promotion of the “China Study Plan” 青年漢學家論壇暨“新漢學國際研修計劃”推介會 at the Third Sinology and the World Today conference mentioned the fact that the former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd had used the expression “New Sinology” in 2010, although there was no evidence that either that speaker or others at the gathering were aware of the origin of the term in 2005 or that it underpinned the Australian Centre on China in the World that I had founded. Later Rudd himself would inexplicably use the term 新漢學, seemingly oblivious to its history. This was more than disappointing. Then again, don’t we live in an era of disappointment?

So, what exactly is “new” 新 about China’s officially condoned Sinology? In the first place, any program that encourages the study of classical and literary Chinese should be looked upon favourably, and without doubt there is much outstanding scholarship being done in the PRC. It is also marvellously convenient these days for students to study the various modalities of Chinese (even without the aid of AI). However, judging from the past, Beijing is likely to be particularly interested in supporting and gatekeeping a kind of Chinese Studies that is, to use their loaded terms, “correct” 正確, “objective” 客觀 and “scientific” 科學. Those familiar with party parole, not to mention party-state practice, will readily appreciate the gloomy significance of such language for it mitigates against pluralism, healthy debate and enlivening differences of opinion.

Q:In 2005, you published On New Sinology, advocating an academic approach that combines modern disciplinary methods with traditional Sinological training to more comprehensively understand contemporary China and its cultural, historical, and intellectual traditions. What is unique about conducting research using the methods and perspectives of New Sinology?

A: In particular, New Sinology has promoted the study of China and its living traditions in the context of the economic transformation and global influence both of China Proper, as well as that of Hong Kong and Taiwan. Over the post-Mao decades, this “Chinese world” has experienced a cultural and intellectual efflorescence that, were it not for the constant interference of and censorship by the Communist Party, would be unique in modern Chinese history.

During the 1990s, the Chinese Communist Party had formally declared that after decades of radical social, political and economic change, it was now “bidding farewell to revolution” and that as a “responsible ruling party” (or a “party for all the people”) it would continue its quest for economic modernisation and global power while reaching a new accommodation with both the country’s imperial and republican pasts. During what I called this “reconciliation of history”, the Chinese party-state reoriented itself to claim a new dominion over China’s past, while rigorously re-affirming its sole right to determine both the nature and contents of China, Chinese culture, thought and history, as well as Chinese identity. This ambitious program was integral to Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin’s “Important Thinking Regarding the Three Represents”, announced in 2000. It would be the basis of the “Two One Hundred Years” timetable for the Party in the twenty-first century first mooted by Hu Jintao and it is the bedrock of the worldview inherited and elaborated by Xi Jinping, a leader who when he came to power in 2012 in effect also announced a truce — and has worked to achieve something of a rapprochement — between the radicalism of the Mao-Liu era (1949-1978) and the Deng-Jiang-Hu decades (1978-2012).

From the 1990s, as China was embraced on the world stage, business, diplomatic and academic exchanges and enmeshing flourished. It was at this juncture that I contemplated the educational environment of my own university and of Chinese Studies in Australia more generally. Years of our own neoliberal “market reforms” had transformed tertiary education. As quasi-business enterprises loosely based on market principles, universities had without doubt become more accessible to a greater number of what were now dubbed “customers”, but as access expanded so did the burden of “user-pays debt”. Higher learning was now primarily seen as a pre-career move that opened paths to future gainful employment. Academic work flourished with the support of a research grant system and the number of undergraduates swelled. However, as contemporary China embraced the past in striking new ways, I felt that, apart from the established disciplines and new intellectual paradigms favoured by the global academy, it was more urgent than ever for students of China and the Chinese world (or, rather, the realm which uses Chinese languages to make meaning of and for the world) to have access to a kind of updated Sinological training that could also equip them to engage with that country’s boisterous lived reality as well as its intellectual and cultural vitality, something that, from the 1990s, I dubbed “The Other Chinas”. My concern in this regard was further fuelled by the fact that, even as the numbers of economists, anthropologists, political scientists, sociologists etc working “in the field” proliferated, cuts in basic language courses, in particular those in literary/classical Chinese, and undergraduate humanities subjects, left many of these well-honed and generously funded disciplinarians sub-literate or semi-literate at best in the Chinese language. Many could mine their discipline-bound subjects with aplomb despite the fact that they were incapable of a more grounded, meaningful and equitable engagement with the society with which they were dealing (see Misplaced Faith in the Social Sciences & the Abiding Lessons of New Sinology). Certainly, China was a profitable “data point” but not necessarily of sui generis value or significance. As in the days of yore, during the bullish years of globalisation “China” was all too readily reduced to being a footnote in the grand narrative of Euramerican academia and its provincial concerns (see my 1999 essay Conflicting Caricatures).

Paradoxically, among all of the other demands of modern university study, it seemed important that at least some students should be trained in aspects of China that could be encapsulated in the old expression 文史哲 wén-shǐ-zhé — the literary, historical and philosophical tradition — so that they could appreciate the vast changes unfolding in the Chinese world, and perhaps even themselves aspire to the kind of “comprehensive knowledge” that remains deeply admired in China (see Jao Tsung-I on 通 tōng — 饒宗頤與通人; and, China Watching in the Xi Jinping Era of Blindness and Deafness).

In advocating New Sinology I was suggesting a form of academic Sinology that combines a fluency in the practices of the “China Studies” that developed during the first Cold War and the academic disciplines that have flourished in academic institutions world wide since WWII. New Sinology engages equally with Official China via its bureaucracy, ideology, propaganda and culture, as well as with the Other Chinas — those vibrant and often disheveled worlds of alterity and possibility, be they in the People’s Republic, Hong Kong, Taiwan, or around the globe.

Q: From the China Heritage journal, it seems easy to discern some characteristics of New Sinology, and it also appears that the research methods of New Sinology run through your academic career. Is this right?

A: As for the abiding relevance of my approach today, early in the Xi Jinping era I observed that:

“Xi Jinping’s China is a gift to the New Sinologist, for the world of the Chairman of Everything requires the serious student of contemporary China to be familiar with basic classical Chinese thought, history and literature, appreciate the abiding influence of Marxist-Leninist ideas and the dialectic prestidigitations of Mao Zedong Thought. Similarly, it requires an understanding of neo-liberal thinking and agendas in the guise of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics 具有中国特色的社会主义. Those who pursue narrow disciplinary approaches to China today serve well the metrics-obsessed international academy, but they may readily fail to offer greater and necessary insights into China and its place in the world.”

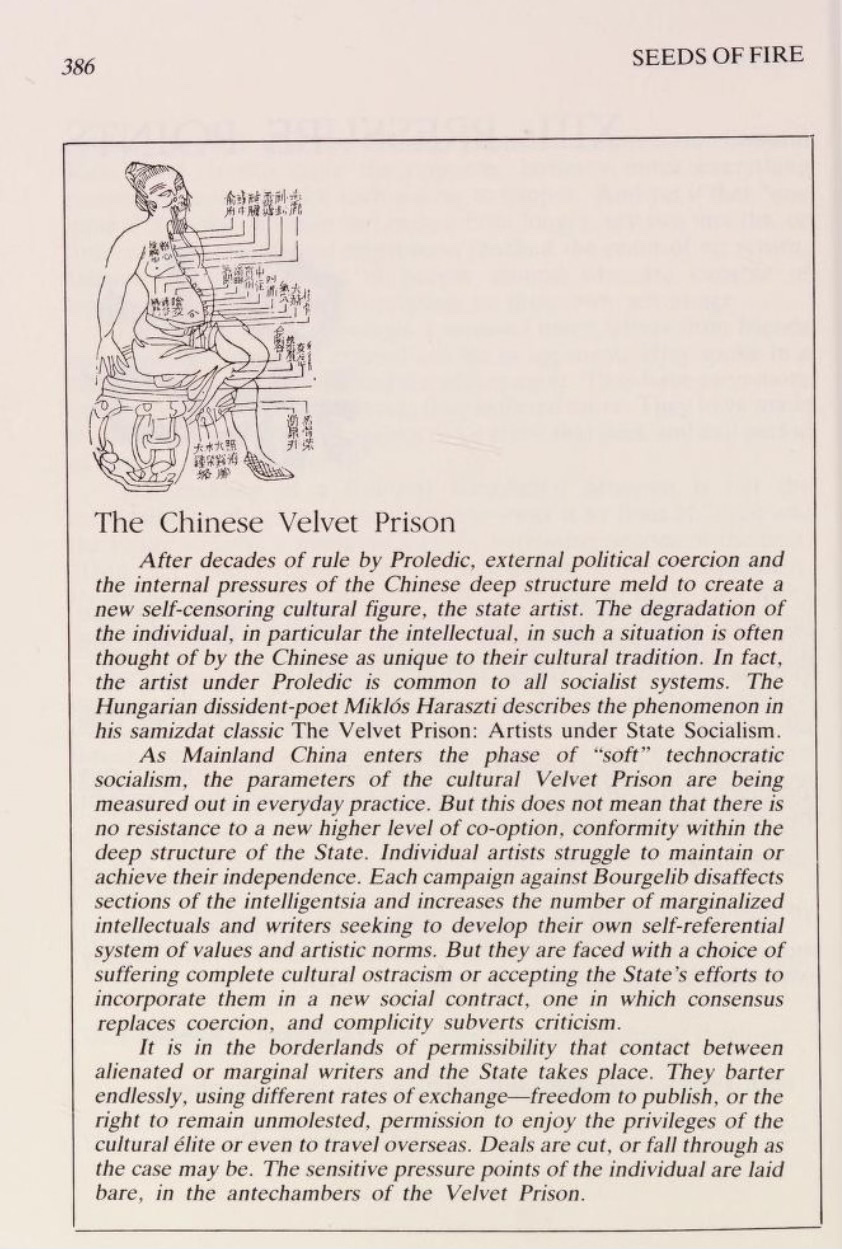

China’s “velvet prison” is now built out a well-funded cultural and arts scene that is au fait with the latest international fashions and technical achievements; an academic world that was long ago brought to heel and sated on official largesse; a publishing world that polices itself (with the help of tireless editors and alert readers); a boisterous online realm kept in line by 24/7 vigilance and vigilantes; and a cadre of cultural creators and online influencers, both Chinese and foreign, who have internalised China’s mature regime of self-censorship (see Less Velvet, More Prison). There’s even enough space in the “iron room” for a touch of transgression, that is those creators who skirt the permissible and who are “naughty but not dangerous”. The Yin-Yang Nation that I have known for half a century is reaching ever-new heights of efficacy and sophistication. How other autocrats must envy it.

Since 2025 marks twenty years since I first advocated New Sinology, a particular focus of China Heritage this year has been celebrating this anniversary. I hope to add this interview to the list of works being published this year.

But, back to the Xi Jinping era, here I would add that when it comes to Beijing’s present attacks on “Historical Nihilism” — that is its decades-long official campaign to undermine historical fact and narrative truth that actually began with Deng Xiaoping and his comrades in 1978 (see my 1993 essay History for the Masses) — I believe that it is incumbent upon those who are interested in pursuing a serious engagement with contemporary China, be they Chinese or non-Chinese, to emulate the spirit of independence and intellectual rigour championed by Chen Yinque (陳寅恪, 1890-1969, aka Chen Yinke), both in the epitaph he composed for Wang Guowei (王國維, 1877-1927) in 1929 and in his principled rejection of the blandishments of Mao Zedong in 1953, on the eve of the devastation of Chinese scholarship (for more on these significant moments in China’s modern intellectual history, see The Two Scholars Who Haunt Tsinghua University; and, 1954 — China’s Dark Enlightenment, Hu Shih & the Nobility of Failure).

Recently, when marking the September 2025 Victory Day celebrations in Beijing I remarked that:

“To have a meaningful intellectual, scholastic or cultural engagement with China and the Sinophone world today requires an effort to study modern history, both as seen in the funhouse mirror of the Communists and their institutions, and as appreciated by independent-minded scholars, analysts and media commentators wherever they may be. To accept The China Story touted by the party-state — one that is meticulously curated and constantly policed — regardless of whether it is for personal, or professional convenience, is to be a willing collaborator in an Empire of Lies.”

I would suggest that a new sinological approach is a necessary prophylactic that helps us guard against the glitzy, well-funded, siren allure of China’s party-state and its logorrheic nonsense.

Q:Another significant characteristic of your academic research is the perspective of Soviet and Eastern European dissident intellectuals. In the 1970’s, most Chinese people hadn’t even heard of Vaclav Havel. How did you come to notice Eastern European writers?

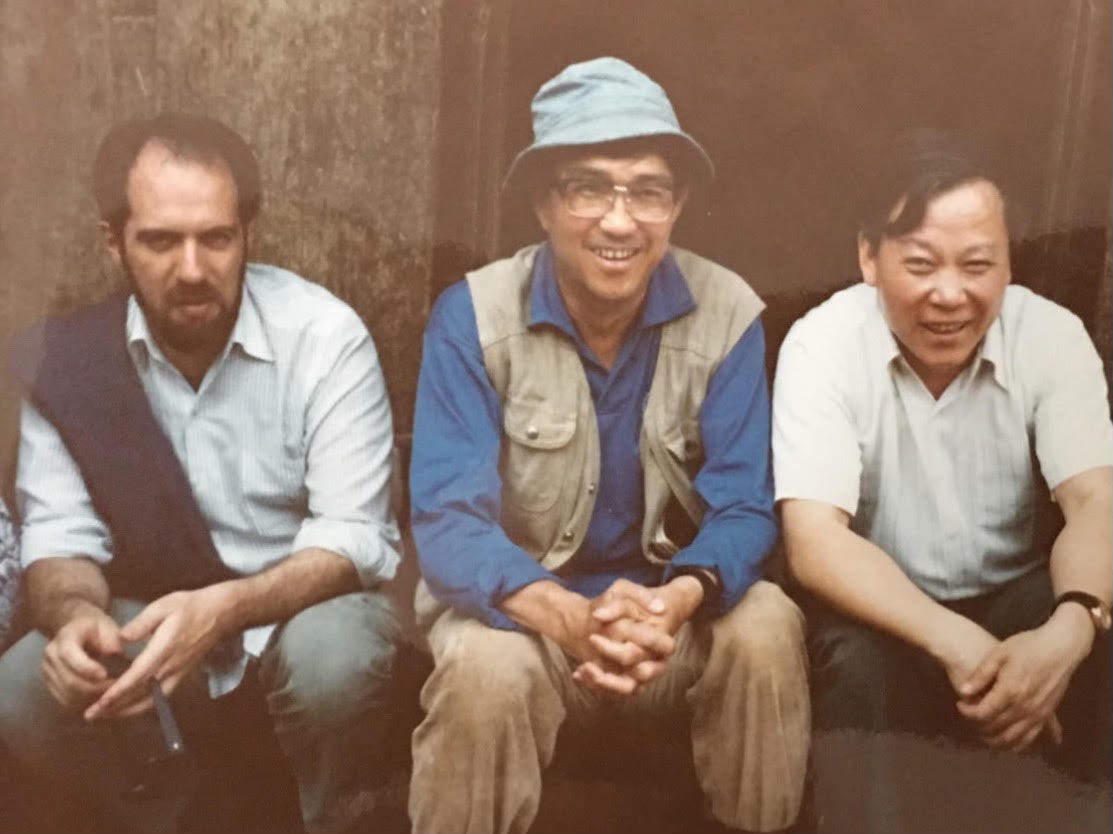

A:My interest in Soviet and Eastern European writers dates back to the 1970s and I began taking serious note of them in 1975. As a twenty-year old student in late-Maoist universities, first in Shanghai and later in Shenyang, we studied some key Stalin-era cultural doctrines and Soviet literature; we were also introduced to the supposedly wayward ideas of the post-Stalin “Soviet revisionists”. In classes on the International Workers’ Movement we learned about the Comintern and the Chinese Communist Party’s Nine Critiques 九評 of the Soviet Union. Our literature and arts courses focussed in particular on the “two-line struggle” 兩條路線鬥爭 in culture that dated back to the 1920s. The Soviet Union and Stalinism (which was usually paraded under the more appealing guise of “Leninism”) were a constant feature of that decades-long contretemps. To overlook or ignore the Russo-Soviet aspect of revolutionary China (that is China from the Late Qing) at best leaves one purblind. (I would note, parenthetically, that with the Sino-Russian comity under Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin, things have, in a sense come full circle. See We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again.) When I started working in Hong Kong in the summer of 1977, I began filling some of the blanks in my education, as well as trying to correct some of the fallacies. Soviet dissident and Eastern European writers were essential guides, and they and their work were known to my colleagues, academics and some younger cultural figures in the British colony. Writers like Clive James and Robert Conquest were also a crucial influence on me at that time, as were Hong Kong mentors like Lee Yee 李怡 and my Beijing friends, Gladys and Yang Xianyi 楊憲益, as well as Wu Zuguang 吳祖光, a playwright and the Master of Layabout Lodge 二流堂.

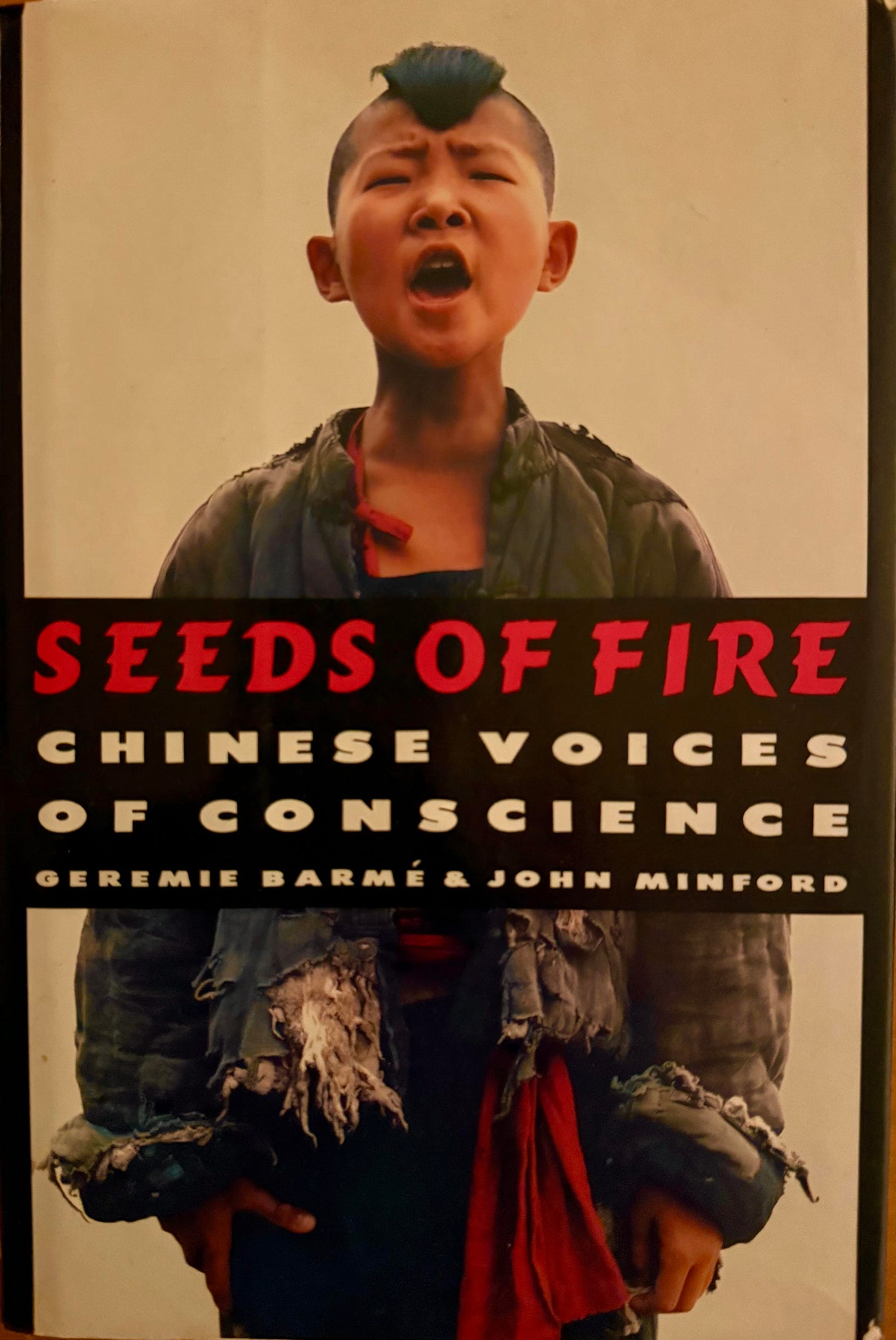

I perviously mentioned Seeds of Fire: Chinese voices of conscience (1986; 2nd ed. 1988) to you. Edited with John Minford and dedicated to the fiftieth anniversary of Lu Xun’s death, that compendium was deeply influenced by ideas and writers in the Soviet cultural sphere, including those current in the Eastern Bloc. Seeds actually grew out of a project called Trees on the Mountain, one initiated by John Minford, then head of the Research Centre for Translation at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and editor of the translation journal Renditions. In the early 1980s, John saw that an interflow of literature, ideas and cultural aspirations was creating what he called a “Chinese commonwealth”, one that included Hong Kong, Taiwan, mainland China and overseas writers. Trees, published in 1983, was the first attempt to bring that world into “conversation” through translation (see: Renditions—A Gateway to Chinese Literature and Culture). Our work was also influenced by my views of the Spiritual Pollution Campaign launched by Beijing at the time. In all of these ventures, translation, editorial commentary and the introduction of clashing ideas and ideological contestation were of vital importance; we were above all attentive to conflicting voices of Chinese writers and thinkers, unofficial as well as official. This was part of an attempt to provide our readers with a more comprehensive, even holistic view of the times. Throughout, however, we kept in mind the haunting message of “A Spectre Prowls Our Land” 一個幽靈在中國大地遊蕩, a poem published by the Sichuan writer Sun Jingxuan 孫靜軒 in 1980 the opening lines of which are: “A loathsome spectre/ Prowls the desolation of your land…”. Decades later, in 2017, I would quote Sun when discussing the impending doom of Hong Kong (see Cauldron 鼎, the introduction to the series Hong Kong Apostasy).

Seeds was followed by books that continued and extended its arguments. These include New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, edited with Linda Jaivin (New York, 1992) and Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader (Armonk, NY, 1995). The 1995 documentary film Gate of Heavenly Peace is, to my mind, part of that body of work. The next volume in the series was In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture (1999), and it was followed in 2003 by Morning Sun, a documentary film focussed on the history and culture of the Cultural Revolution which we framed using various cultural devices that, in hindsight, were themselves rather “new sinological”. It was not long after Morning Sun premièred at the Berlin International Film Festival that I launched the e-journal China Heritage Quarterly (originally China Heritage Newsletter) with Bruce Doar, a scholar of prodigious intellectual range and depth. Then, in May 2005, I released my “New Sinology manifesto”. For the next five years, China Heritage Quarterly was the platform for its practice and, from 2007 to 2012, I published some twenty themed issues of the journal.

Q:I’m surprised that you were already using Eastern European thought to analyze China in the 1980s?

A:You shouldn’t be. Eastern European and Soviet writers had a particular influence on my work from the late 1970s and, as I wrote in the Introduction to In the Red:

“In attempting to discuss this [i.e. China’s] shifting cultural landscape, I have often had recourse to both the writings of China’s small but significant group of ‘independent’ or ‘liberal intellectuals,’ ziyou zhishifenzi, and works by (former) Eastern bloc and Soviet writers and scholars whose insights provide a refreshing, critical angle on the paradoxes of terminal socialism. Miklós Haraszti, Alexander Zinoviev, Norman Manea, Mikhail Epstein, and Svetlana Boym, as well as the South African novelist J. M. Coetzee and the Yugoslav writer Danilo Kiš, all find a place here as we discuss issues that are peculiar to reformist China but that also confront and confound a broader humanity.”

I would add that, from the time I came into direct contact with Chinese writers and thinkers in the late 1970s, I often found their insights, although poignant, to be somewhat overly limited to their particular circumstances, history and the conditions of China. At the same time, older members of the intelligentsia who had been educated under the Republic and had experienced the PRC’s extreme “Soviet lurch” and the Thought Reform movement of the early 1950s, were constantly reminding me of the Soviet dimension of China’s modern history. Among others there was Ai Qing 艾青 and Ding Ling 丁玲, both Yan’an-era cadres, and the younger famous literary figures Liu Binyan 劉賓雁 and Wang Meng 王蒙. As many others have noted, the “China Obsession” 中國情意結 often confines even the smartest analysts to the sometimes narrow confines of China-specific issues. Soviet and Eastern European dissident writers broadened the scope of my understanding of China’s state socialism, the Maoist experience and the unique aspects of revolutionary China, all of which became important concerns of New Sinology. My advocacy of New Sinology is, therefore, by no means an endorsement of “Chinese exceptionalism”.

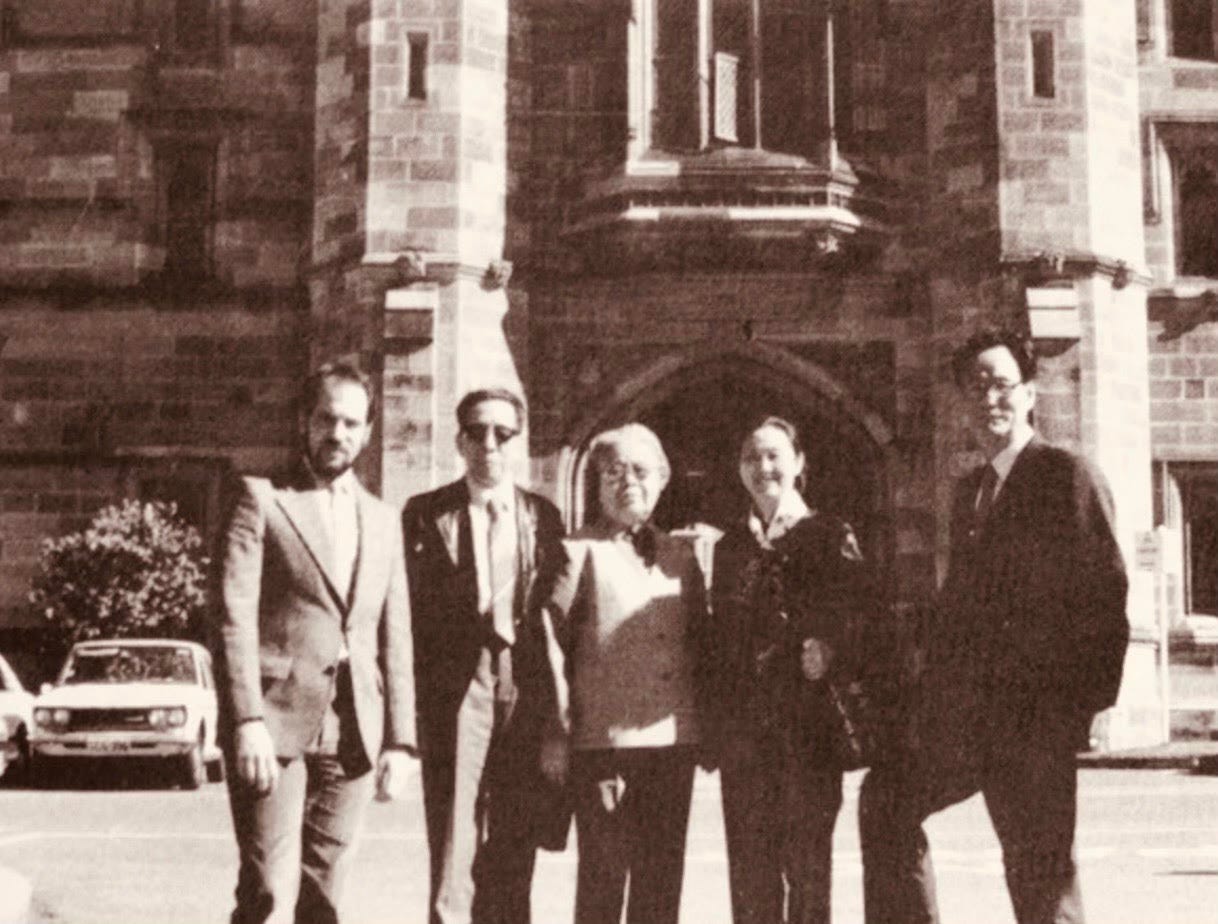

You’ll note that the first chapter of In the Red — “The Chinese Velvet Prison” — builds on the ideas of Miklós Haraszti, a Hungarian dissident who first featured in my work in 1988. At that time we had included references to Haraszti’s then-new book The Velvet Prison: artists under state socialism in the US edition of Seeds of Fire. It was Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys), my mentor — he was both my undergraduate language teacher and my doctoral supervisor — who introduced me to Haraszti’s work in early 1987. [Editor’s Note: For more on Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys), see One Decent Man, a review-essay by Barmé, published in the June 28, 2018, issue of The New York Review of Books, in which he discusses Philippe Paquet’s biography of Simon Leys: Navigator Between Worlds. The article reviews the life and scholarly contributions of Belgian-Australian Sinologist Pierre Ryckmans, focusing on his incisive critiques of Chinese classical culture and Maoist politics. In his review, Barmé reflects on his experiences as Ryckmans’ student, recounting their correspondence during China’s turbulent 1970s and highlights how Ryckmans used Sinological insights to expose the authoritarian nature of Mao’s regime. The review not only praises Ryckmans’ integrity and academic contributions but also underscores his lasting significance for contemporary students of China.]

I should also add that, back in 1983, John Minford had introduced me to The Captive Mind. Written by Czesław Miłosz and published in 1953, The Captive Mind remains one of the most insightful studies of resistance and complicity under socialist state authoritarianism. Stephen Soong 宋淇, John’s colleague and mentor at Chinese University, published a translation of the book under the title 攻心記 in 1956 (攻心 being an ancient term for “psyop”). Around the time that I encountered Miłosz in Hong Kong, I also happened to meet Dong Leshan 董樂山 in Beijing. Leshan was the mainland translator of George Orwell’s work, among other things (see Nineteen Eighty-Four — Simon Leys on George Orwell in 1984.)

Here is a copy of the page in Seeds of Fire (1988, 2nd. Edition, published in the US) that features Miklós Haraszti. I wrote this short editorial comment in mid 1987, shortly after reading The Velvet Prison:

Please note. In the following passage about “The Chinese Velvet Prison” you’ll encounter a few of the neologisms that we coined for Seeds, something we did in the style of “nadsat” — the argot invented by Anthony Burgess for his novel Clockwork Orange — in an attempt to reflect something of the “Orwellian” strangeness of Communist Party language, or what I would later refer to as “New China Newspeak” 新華文體. Two of our neologisms appear in this passage: there’s “Proledic”, short for “the dictatorship of the proletariat” 無產階級專政; and, “Bourgelib”, from “bourgeois liberalisation” 資產階級自由化, a term that had a particularly menacing significance 1980s and early 1990s’ China.

Q:I previously wrote a report titled “How Havel Was Introduced to Chinese Intellectual Circles and Influenced Generations of Intellectuals: Interviews with Liu Kang, Andrew Nathan, and Cui Weiping.” It seems that the ideas of Eastern European writers began to spread in China after 1989, but in Hong Kong, it appears to have happened earlier, with scholars already disseminating the ideas and works of Eastern European writers before 1989. You were working in Hong Kong at that time, weren’t you?

A:Actually, I first wrote about Miklós Haraszti in October 1987. It was in one of the series of essays on Chinese politics and culture that I published in the Hong Kong monthly The Nineties from 1986 to 1991 (I had worked for The Seventies Monthly, the predecessor to The Nineties, from 1977 under the mentorship of Lee Yee, whom I mentioned earlier). My short essay on Haraszti spoke about what I dubbed China’s “culture under house arrest” 軟禁文化 (see 社會主義的“軟禁文化”:讀哈拉茨蒂的《畫地為牢》). It was a companion piece to another article that focussed on Bo Yang 柏楊, a Taiwan friend who was then famous for The Ugly Chinaman, and a unique moment of “pluralism” on the mainland in 1986. That rather halcyon period was followed by students in Shanghai protesting in favor of press freedom in late 1986 and the subsequent purge of Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang. As things turned out, all of that merely adumbrated the tragedy of 1989 (see 《寬容殺與柏楊熱》, as well as the Archive in China Heritage for my other Chinese-language essays and books, including the first ever interview with Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波, the delightfully garrulous cultural upstart whom I met in late 1986).

As I noted earlier, I had worked at The Seventies for a few years after leaving China in 1977 and here I must digress to note the significance of Hong Kong itself. “Mainland blindness” has for decades led to a certain offhand attitude when it comes to appreciating the former British colony as a major cultural and intellectual entrepôt in the Chinese world from the 1940s right up to its precipitous fall in 2020 (see the series Hong Kong Apostasy). The territory’s writers, academics, students and translators were alert to the dissident writers of the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc from the 1950s, as Stephen Soong’s translation of Miłosz indicates. Among them there were also avid readers of Encounter magazine, a vital journal of record of the activities and writings of European and Russian dissidents founded in the early 1950s. Encounter remains an essential, and highly readable source, even if its reputation is tainted by its association with the CIA’s Congress for Cultural Freedom. I was introduced to it in Hong Kong and, in fact on reflection, it was perhaps my encounters with leftist writers and independent thinkers as well as my experiences in Hong Kong, with its admix of tradition and the modern, Cantonese and Mandarin, classical prose and modern inventiveness, the global, Taiwan, and the mainland, that really gave birth to New Sinology. One of the many interesting journals produced at the time was To-so 抖擻, founded in 1974.

Chinese intellectuals and Western academics mostly treated Hong Kong as a place of transit, a source for research information on the Mainland and, for mainland academics and writers, a place to make a bit of quick money by publishing work in local journals. Generally speaking, they tended to overlook, or were ignorant of, its lively cultural and intellectual life. Ironically, mainland writers and intellectuals were far too ready to dismiss the only part of the Chinese world in which real cultural exchange and conversation was, for a few precious decades, really possible. One hopes that more scholars will finally turn their attention to the unique role that Hong Kong played as a centre of “Chinese cultural exile”, invention and discovery (one friend, the intellectual historian Sebastian Veg, has been engaged in this kind of work for some time). In In the Red I write at some length about what I call the “Kong-Tai Ark” 港臺方舟 and how Hong Kong and Taiwan helped the mainland in a myriad of ways, from commerce to culture, to “rediscover” itself from the 1980s, aiding thereby to lay the foundations for the efflorescence that we’ve seen since the 1990s.

..Q: In the online journal China Heritage, I noticed that you have written many articles about Eastern European, Soviet/Russian thought and Chinese resistance. In your Contra Trump series, you also draw on Miklós Haraszti’s ideas. What significance does Eastern Bloc hold for today?

A:In China Heritage Quarterly (the precursor to China Heritage) and China Heritage, many articles explore themes of socialism, authoritarianism, and resistance through the works of Eastern European, Soviet, and Russian writers, including Anna Akhmatova, Nadezhda Mandelstam, Alexander Zinoviev, Czesław Miłosz, Václav Havel, Isaiah Berlin, Leszek Kołakowski, Dmitri Shostakovich, Masha Gessen, Alexander Dugin, and others.

To my mind, the socialist market environment of the Deng-Jiang-Hu authoritarian era (1978-2012), and its careening forward path between hardline repression and relative liberalisation, echoed somewhat the “socialism with a human face” of Alexander Dubček and his colleagues. Although that phase of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia was short lived, the oppositionist culture that grew out of it in the 1970s and 80s, including that of Havel and his fellows, finds an echo in developments in reform-era China. That’s why I was drawn to writers like Miklós Haraszti in the 1980s.

Under what I call the Empire of Tedium of Xi Jinping (2013-), which in many ways is a kind of “restoration” within the Chinese system, and its harder-line surveillance socialism, I often feel that Soviet-era Russian dissidents are more of a touchstone (see We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again). Under Xi, the soft dissent of the Eastern Bloc is easily corralled or crushed by a state that delights in mass cultural performance, is the enemy of civil society and pursues its obsession with wealth, power and global influence. Here I would hasten to add that, in my view Cold War 2.0 actually started in June 1989 (see Back When the Sino-US Cold War Began).

Q: I noticed that you also use an Eastern Bloc perspective to examine contemporary America?

A:Over the years, China Heritage has noted some of the discomforting parallels between the histories of modern China and America. We have pursued our parallax bilateralism in the spirit of what I think of as “Larrikin Sinology” (“larrikin” is Australian slang word roughly equivalent to the Chinese term 潑皮) — the wary study of a serious subject undertaken in an irreverent mood. In my pursuit, I employ some of the old skills of China Watching to watch America.

I first looked through my Sino-American lens when I published A Monkey King’s Journey to the East on the eve of Trump’s inauguration as president in January 2017. During Trump’s first term, I commented on the ways that both Official America and Official China twist modern history to serve their imbricated political ends — see, for example, Mangling May Fourth 2020 in Washington and Mangling May Fourth 2020 in Beijing — and I have observed that:

“Those of us who are inextricably involved with both of those nations while living, for the most part, on the periphery of these cheek-by-jowl empires, have witnessed a decades-long ‘apache dance’.” (Editor’s Note: The “Apache Dance” is a term originating from France, initially referring to a dramatic and intense partnered dance popular in early 20th-century Parisian streets. It mimics the quarrels and physical confrontations between men and women in the Apache gangs, a criminal subculture in Paris’s underclass. The dance features exaggerated, rough movements, often imbued with elements of violence and passion.)

In the wake of Trump’s electoral defeat in 2020, I launched Spectres & Souls — Vignettes, moments and meditations on China and America, 1861-2021. This was a yearlong discussion in which I suggested that many of the spectres and shades, as well as the enlivening souls and lofty inspirations, that asserted themselves both in China and the United States in 2021 could fruitfully be considered in the context of the 160-year period starting in 1861. In November that year, the successful Xinyou Coup 辛酉政變 at the court of the Manchu-Qing dynasty that had ruled China for two centuries ushered in a short-lived period of rapid reform, one that, in many respects continues to this day, even as it may be faltering in recent years. While, in February 1861 on the other side of the Pacific Ocean seven slave-owning states broke with the Union that had been established under the Constitution of 1787, resulting in a four-year civil war. The successful conclusion of that war saved the Union, but the failure of the subsequent era of Reconstruction had profound ramifications for the state of that union, and the United States of America generally.

Just before Donald Trump’s second electoral victory in November 2024, I launched the series Contra Trump — America’s Empire of Tedium. In it, I refer both to Xi Jinping’s China and to Trump’s America as “‘empires of tedium” 無可奈何的江山. That is to say, regardless of their formidable strengths, be they overlapping or contrasting, the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America are in a circuit of history from which they both may, eventually, grow out of or escape from. But to achieve that kind of velocity of positive change will require the painstaking and tiresome work of facing the tedious realities of the past along with the crippling realities of the present. For those mindful of American and Chinese socio-political change over the past sixty years, the recidivism of the 2020s may be tedious, troubling and tenebrous, but it is not entirely surprising. In both cases, the inevitable biological attrition that faces their respective “Great Men” may promise a brighter future. Or not.

That is why, more recently, I have returned to the ideas of Miklós Haraszti, but this time in my Contra Trump series (see: The Lessons of Orbán’s Hungary for Trump’s America, according to Miklós Haraszti). And, of course, Jason Stanley and Timothy Snyder, US scholars known for their work on fascism and Eastern Europe, also feature in Contra Trump. As I note in the introduction to Contra Trump:

“Given the haunting parallels between Trump’s USA and Xi Jinping’s Chinese People’s Republic, I have even suggested that it is time for a new academic and journalistic analytical approach to the Sino-American conundrum. I call it ‘Whataboutism Studies’, a somewhat different form of ‘Both-Sidesism’, and it explores how the Horseshoe Theory might offer a useful perspective on the bilateral apache dance. That theory suggests that the extreme right — in this case ‘American Fascism’ — and extreme left — China’s surveillance state socialism, bend toward each other like the ends of a horseshoe. Even though false equivalencies abound in US-China discussions, real equivalents deserve attention, in particular in the post-COVID era when political and economic pilgrims seek influence as New China Experts.’ (Editor Note:The “Horseshoe Theory” is a political theory suggesting that extreme political ideologies, such as the far right and far left, though seemingly opposed, may converge in certain characteristics, behaviors, or goals, forming a structure resembling a horseshoe—where the two ends appear far apart but bend closer in certain aspects. Proposed by French scholar Jean-Pierre Faye in 1996, the theory is often used to explain how extremism manifests similar traits in practice (e.g., authoritarian tendencies, opposition to liberal democracy, or suppression of dissent). For instance, far-right nationalism and far-left collectivism may both resort to strong control or exclusion of dissent. The theory offers a perspective for analyzing the political spectrum but has been criticized for oversimplifying complex political positions.)

Q: Do you find similarities between China and the United States?

A:As she walked down Little Collins Street in Melbourne with her arm in mine after dinner on the last night of her visit to Australia in May 1985, the eighty-one year old writer Ding Ling 丁玲, whom I had first met and later interviewed in 1978, told me that experience had taught her that you had to live long enough to see your enemies confounded and for things come full circle. Purged in 1955 for operating an “anti-Party clique” and not rehabilitated until 1979, Ding only recently had had the satisfaction of seeing her old nemesis Zhou Yang 周揚, with whom she had spared since their days in Yan’an, criticised and her reputation as an unwavering Party loyalist further burnished.

Since the rise of Xi Jinping in 2012 and following the advent of Donald Trump in 2015, I have often thought of Lao Ding’s words. In a way, things have indeed come full circle. I find some evidence for this the fact that among China’s soi-disant “liberal” intellectuals, many have turned to Trumpism .Some of the most vocal in this claque — men and women who were Red Guards in their youth — are people that I have known for years. Over the last decade, their statements on social media in and outside China have been vitriolic in support for an American politician whom I previously compared to Mao Zedong. Just as in their Maoist youth, Trump’s Chinese cult followers have a vicious topsy-turvy view of reality; they revel in the kind of “lack of empathy” that had been a hallmark of their youth and China’s extremist past.

On 15 September, my friend Zhang Qianfan 張千帆, a professor of constitutional law at Peking University Law School, published a commentary in the Financial Times on American gun culture and the death of Charlie Kirk, a noted MAGA provocateur and a man who famously muddied the waters around the idea of empathy. The essay elicited an explosion of hateful comments from the Old Red Guard Trumpists 川粉 in China and their coevals in America. Although Shi Tao 師濤, a former dissident jailed for advocating democracy, was born too late to have been a Red Guard, yet it was in the spirit of the past that he reported Professor Zhang to the American Embassy in Beijing with a plea that the academic be banned from entering America in the future. Shi Tao’s behaviour both reflected China’s ingrained culture of snitching and chimed with US Vice-President J.D. Vance’s appeal to “get involved” by ferreting out people who had been inadequate in their reverence after Kirk’s death and to “[call] them out, hell, call their employers”.

As I argue in Contra Trump, the US administration is increasingly in sync with China’s socialist commodity surveillance state — In the Red I described reformist China as being a polity in which comrades were encouraged to become consumers without ever being allowed to evolve into citizens. The branches of the “horseshoe” are growing closer to each other: Word Crime 以言獲罪, CrimeThink 思想犯罪, ThinkPol 思想警察, DoubleThink 雙想, Historical Nihilism 歷史虛無主義 — the panoply of Orwellian grotesques that have marked state socialist regimes since the October Revolution over a century ago and characterise, too, Xi Jinping’s rule — now thrive in Trump’s America. Mirabile dictu: it is all being cheered on by a nasty clutch of former Red Guards who have simply regressed into their feverish adolescence.

In 1987, Simon Leys observed, Eastern European dissidents had long been “charting the topography of a grim new world which we may well be condemned to inhabit tomorrow”. Now, nearly half a century later, we can see how prescient he was.

I am grateful to Boston Review of Books for taking such an interest in my work and for allowing me to explain myself at such length. Thank you.

Appendix:

Geremie R. Barmé’s works focus on Chinese culture, politics, and historical transformations, integrating Eastern and Western intellectual perspectives to deeply analyze the contradictions and dissent within China’s modernization process. His major works and projects include:

Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience (1986, Hong Kong, first edition; 1988, New York: Hill and Wang, expanded edition).

An early work collecting the voices of Chinese conscientious intellectuals, exploring dissent and resistance in the early reform era.On The Eve: China Symposium ’89, Bolinas, California, 27-29 April, 1989, edited and annotated by Geremie R. Barmé, cyber-publication in 1996, online at: www.tsquare.tv. A volume of speeches and essays by Chinese cultural figures and American China scholars on the state of China, recorded as the Beijing Protest Movement unfolded in late April 1989.

1989, Three Studies: Liu Xiaobo: Confession, Redemption and Death (1990); Using the Past to Save the Present; Dai Qing’s Historiographical Dissent (1991); and, History for the Masses (1993)

New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, edited with Linda Jaivin (New York, 1992).

The Gate of Heavenly Peace (1995, documentary film, for which Barmé was the chief academic consultant, principal scriptwriter, and website founder).

Examines the history and cultural context of the 1989 Tiananmen Movement through oral history interviews and documentary footing, analyzing in the process the complexities and consequences of China’s democratic movement. With veteran film-maker colleagues Gate was a work that built on the polyphonic and the critical style of Seeds of Fire.Shades of Mao: the Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader (Armonk, NY, 1995), an examination of the new Mao cult and the nationalist strain of the 1990s. At a conference held at Harvard University to mark the centenary of Mao’s birth, Barmé presented his findings regarding the popular Mao cult that flourished in the wake of the calamitous events of 1989, and response of many of the senior academics present — noted political scientists and historians — was generally patronising and dismissive.

The Garden of Perfect Brightness, a Life in Ruins, The 57th George Ernest Morrison Lecture, December 1996; and, Gong Xiaogong, a case of mistaken identity (Wellington: Asian Studies Institute, Victoria University, 1999), a lecture on the burning of the Garden of Perfect Brightness.

The Great Firewall of China, a survey of the state of the Chinese internet commissioned by WIRED and conducted with the oral historian Sang Ye (published in WIRED, June 1997). In this work Sang Ye and Barmé coined the term “the great firewall of China”.

In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999).

Analyzes paradoxes in contemporary Chinese culture, drawing on Eastern European writers (e.g., Miklós Haraszti’s The Velvet Prison) to discuss the cultural landscape of “terminal socialism.” A seminal work, it significantly shaped understanding of Chinese culture during the reform era.An Artistic Exile: A Life of Feng Zikai (1897–1975) (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

A biographical study of Chinese artist Feng Zikai, exploring century long fissures in China’s intellectual and cultural life and the “Middle Path” of a unique artist who also had to face the challenges of living under state socialism, awarded the 2004 Joseph Levenson Book Prize.Morning Sun (2003, documentary film, co-director, producer, scriptwriter, and website founder).

Focuses on the history and culture of the Cultural Revolution. Framed by the films The East is Red 東方紅 and The Gadfly 牛虻 Morning Sun uses archives and personal stories to dissect the era’s social turmoil and ideological impact.China Candid: the People on the People’s Republic, by Sang Ye (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), a continuation of previous work in which Barmé translated oral history interviews conducted by Sang Ye, an undertaking that spanned three decades, from 1985 to 2015 (see also The Rings of Beijing, 2007-2015)

The Forbidden City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008).

Explores the Forbidden City as a symbol of Chinese political and cultural evolution, analyzing its significance in modern China.The China Story Yearbook Series (Founded and Edited: Barmé founded the series in 2012 and edited the first three volumes in the series; see https://www.thechinastory.org/yearbooks/).

An annual publication focusing on contemporary Chinese politics, economy, and culture, offering a multidisciplinary perspective on China’s international influence.The China Story Journal (Founded and Edited: Barmé founded in August 2012, edited until January 2016).

Provides in-depth analysis of contemporary Chinese issues, covering politics, culture, and social changes.China Heritage Quarterly and China Heritage (Edited and developed: Barmé edited China Heritage Quarterly from 2005 to 2012, which from 2016 was rejigged as China Heritage).

Publishes articles on Chinese culture, history, and contemporary issues. Series include “Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium,” “Translatio imperii sinici” (The Continuation of Imperial Thought), and “Homo Xinensis” (The Socialist New Man of the Xi Jinping Era), critiquing the authoritarian tendencies of Xi Jinping’s era and exploring the continuity and transformation of Chinese political culture

And, select translations, lectures, series, edited volumes, as well as collections in Chinese:

The Wounded: Stories from the Cultural Revolution, 1977-78, selected and translated by G. Barmé and Bennett Lee (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 1979), including Scars 傷痕 by Lu Xinhua 廬新華 and The Class Monitor 班主任 by Liu Xinwu 劉心武.

Lazy Dragon, Stories from the Ming Dynasty, translated by Gladys Yang and Yang Xianyi (edited by G. Barmé, Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 1981).

A Cadre School Life: Six Chapters, with the assistance of Bennett Lee (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 1982). In 1989, a revised edition with a foreword by Simon Leys was published under the title Lost in the Crowd: A Cultural Revolution Memoir, by Yang Jiang (Melbourne: McPhee Gribble). A translation of 楊絳《幹校六記》with calligraphy by Qian Zhongshu 錢鐘書.

Xiyangjing xia 西洋鏡下, by Bai Jieming 白杰明 (G. Barmé) (Hong Kong: Po Wen Books, 1981). A collection of essays, film criticism and satire.

Zixingche wenji 自行車文集, by Bai Jieming 白杰明 (G. Barmé) (Hong Kong: Cosmos Books, 1984). Essays and humorous cultural commentaries.

Random Thoughts by Ba Jin 巴金著《隨想錄》, trans. by Barmé (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 1984); and Dissenting from Ba Jin, Far Eastern Economic Review, November 2005, vol.168, no.10, pp.53-55.

The Great Wall of China, edited with Claire Roberts (Sydney: The Powerhouse Museum and Canberra: China Heritage Project, ANU, 2006), an exhibition catalogue.

Australia and China in the World: Whose Literacy?, Inaugural Australian Centre on China in the World Annual Lecture, 15 July 2011.

Telling Chinese Stories, 1 May 2012, which launched The China Story Project.

10. An Educated Man is Not a Pot: On the University, a volume of essays, talks and interviews by Simon Leys on tertiary education edited and introduced by Geremie R. Barmé, launched at the Royal Geographical Society Hong Kong on 13 March 2017 and published online.

11. Cutting a Deal with Xi Jinping’s China; and Ethical Dilemmas — notes for academics who deal with Xi Jinping’s China. The speech with which Barmé launched China Heritage in December 2017 and a follow-up essay on the pitfalls of engaging with the mercurial realities of China’s people’s republic.

12. New Sinology Jottings 後漢學劄記, short essays written in the spirit of New Sinology, encouraging an understanding of the Chinese world that does not artificially sequester an appreciation of culture, thought and religion from an understanding of politics, society and economics. Ours is a form of Sinology that has evolved during the present era of reinvented Chinese traditions; it is an approach that constantly recalls the diverse strains of history and culture that underpin the multiverse of China, a polyphonous world that the party-state of the People’s Republic attempts to dominate, silence, corral or eliminate, without success.

13. Hong Kong Apostasy, a series in China Heritage that takes as its focus the 2019 Hong Kong Protest Movement, featuring in particular local voices and analysis by Lee Yee 李怡. The protests were, in essence, a rejection of the Official China of Xi Jinping and a celebration of The Other China, or “The Best China”, one repeatedly ignored, misunderstood and threatened by the Communist party-state.

14. The Other China is not the China of stentorian slogans, cutting barbs, sarcastic put-downs. It is not the China of clichéd patriotism and exaggerated public performance; nor is it the China of crude stereotypes and bottomless grievance. It is a China of humanity and decency, of quiet dignity and unflappable perseverance. It is a China that finds expression in myriad ways in a country dominated by a political party that would bend all to its will; it is a China that survived the depredations of the Mao era (1949-1978) and increasingly flourished during the decades of reform from 1978 to 2008. The Other China, or what could also be called “Other Chinas”, is not limited to the People’s Republic of China, for it is part of a global culture unique to itself but also with universal aspirations and appeal.

15. Xu Zhangrun Archive (2018-) 許章潤典藏, a collection of annotated translations of essays by Professor Xu Zhangrun, a leading scholar of jurisprudence cashiered by Tsinghua University in 2019.

16. The Tower of Reading 唸樓, guided readings in New Sinology with Zhong Shuhe 鐘叔河, 2024 ongoing.

17. 白杰明, “直指現今,敘諸久遠”, 序許氏無齋先生巨著《戊戌六章》(Chinese)

Great interview. China studies needs more Geremie Baumé’s.