Gail B. Hershatter:The Biggest Challenge Is To Establish Facts

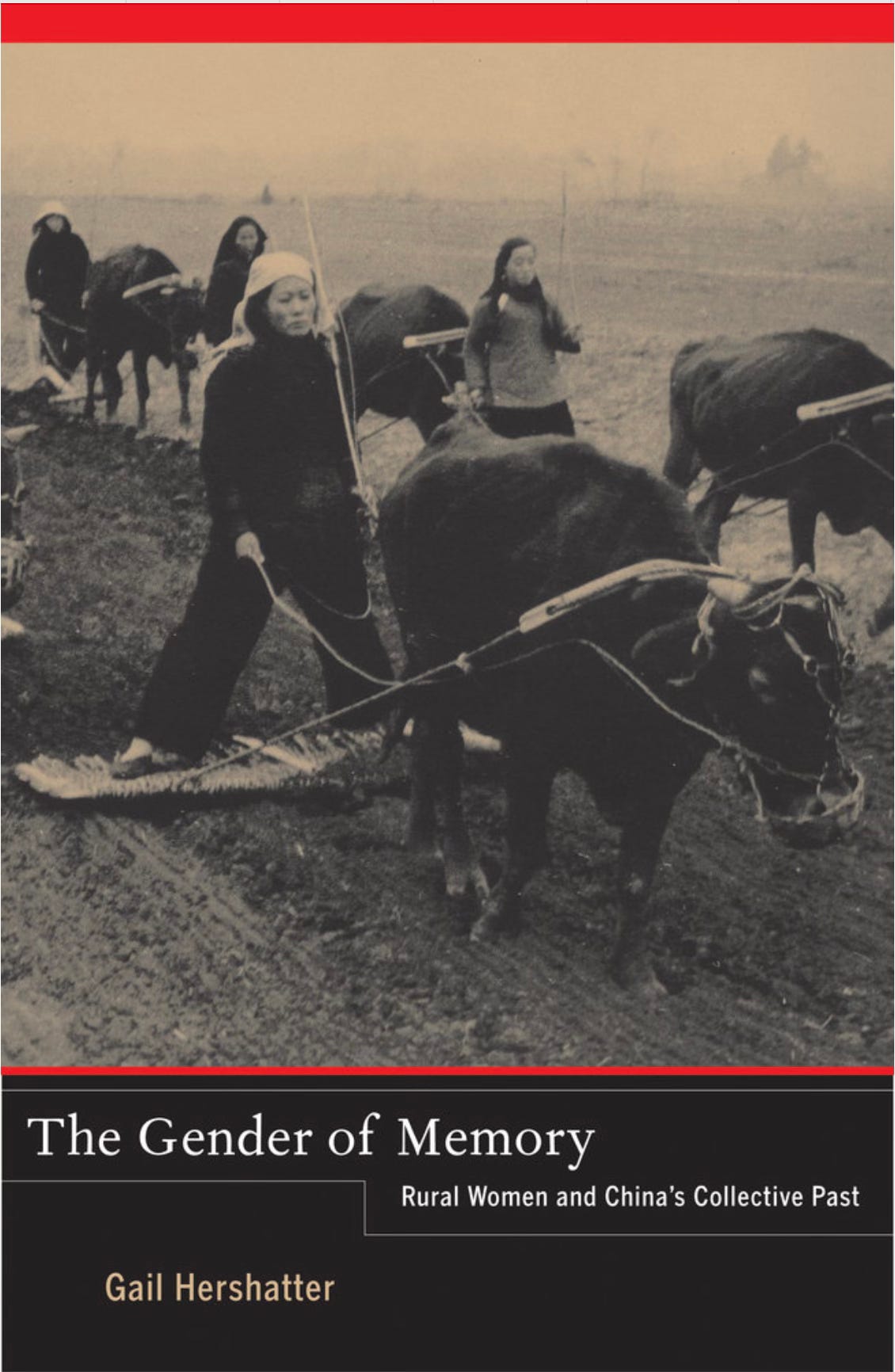

Editor's note: In April 2017, the Chinese version of "The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and the History of China's Collective Past" was published. Professor Gail Hershatter accepted my interview via email. The interview was published in Chinese. English version of interview is published for the first time.

Soon after the intervew , Professor He Xiao was dissatisfied that the new book he published had been deleted, so she put the entire Chinese translation of the new book on the Internet.

Q: 1 You mentioned in your book “Village women, particularly those from poorer households, soon became an important element in the political rituals of land reform meeting. At these meetings women first learned to ‘speak bitterness', the practice that did so much to shape the narratives on which this books draws.”(78)“In Cao Zhuxiang’s village, one household out of forty-two in her immediate neighborhood(east and west village) received the landlord label. the larger administrative village of which it was a part had only four landlords, mainly of the ‘tattered’ variety.”(79)

My question is: all the interviewee are from “poor peasant” or “lower-middle peasant”like Zhuxiang? Is there anyone who is from landlord family or “rich peasant”? What is the meaning of ”The China’s collective past“ in the title?Does it including the class of the landlord?

A: It's a good question. Most of the women Gao Xiaoxian and I interviewed had been very poor before 1949, and were classified as poor peasants or middle peasants during the land reform. There were a few people who were better off, and at least one had married into a landlord family, although she did not tell us that, and in fact was quite angry when someone else in her village did tell us.

However, we were not trying to get a representative sample of people from every class background. What we tried to do was to interview every living woman of a certain age who was still alive in the villages that we visited, and who was healthy enough and willing to talk. There is also the possibility that some people came from wealthier backgrounds but were not willing to talk about it in their stories. But of course it is also the case that the people most ready to talk about how they had suffered before 1949, and how their lives changed after 1949, where those from poor backgrounds.

Your question points up another feature of the land reform in northwest China. This was not a wealthy region, the land was not that fertile, and before 1949 land was not a great investment. The landlord class was relatively small when compared to South China or Jiangnan, and the landlords who did exist tended not to have very big landholdings. Land reform alone did not release enough resources to stimulate rapid development of the economy, but the new state very much needed the revenues from agriculture to underwrite the costs of industrialization. That was one of the reasons, I think, that state authorities moved so rapidly to collectivize the land, so that private landownership was abolished within a few years of land reform. There were political reasons to move in the direction of collective ownership, of course, but there was also the hope that it would help speed economic development.

As for the meaning of the title "Rural Women and China's Collective Past" in my book title, there is a kind of pun here in English that is difficult to translate into Chinese. In English, "collective" can have several meanings. One of them can describe socialist ownership arrangements, or what we would call jitihua 集体化 in Chinese. But "collective" also has the meaning of "shared in common," or gongtong 共同in Chinese. I wanted to capture both ideas. I was interested in exploring the historical time when Chinese agriculture was collectivized. But I was also exploring the past that Chinese from many different backgrounds have in common—the Mao years—and how that past is now understood in the reform era by different groups of people.

Q: 2 You mentioned in your book: “ Women had to be instructed in how to understand and narrate what had happened to them in the past,and cadres had to be taught how to instruct them. ” (78)

The book is based on the memory of 72 women.But how do you make sure their memories were instructed by the state’s ideology ? if yes, how do you recognize the instruction and handle it in your book? ( you talked a little it at first chapter “frame”,but i still want to ask again)

(The research of Prof. James Wertsch is about collective memory and identity. He thinks the national ideology could provide memory template to every generation. The person who controls template controls memory. That is how the power controls everybody’s memory.)

A: This question raises an important issue: how are the memories of individuals shaped by the actions of what I call Big History? By Big History, I mean events that get written about in history books and that usually concern political policies, wars, or rapid social change? When we read history books, and become familiar with an account of Big History events, we often feel that we understand what happened in a particular time and place. But the question that interests me is this: who is having these experiences? And how do these Big History events become modified, or become even more important, or even disappear, among different groups up and down a political hierarchy in a particular time and place?

You asked how I make sure that the memories of the 72 women were shaped by the state’s ideology. But I don't think that there is a simple correlation between official state positions and how individuals understand them. In fact, that is precisely the issue I wanted to explore by interviewing women who lived in rural villages far from the center of power in Beijing. Many policies and initiatives, some of them quite radical, were emanating from the central government of the People’s Republic of China during the 1950s. So my question is, how did people at the grassroots understand that state, and the policy was generated? Did those policies work as they were intended to work in rural villages? What kinds of intended effects, and unintended efforts, did they produce at the local level?

Also, the interviews that Gao Xiaoxian and I conducted raise another important question about how memory works. We were talking to women about events that happened four decades or more after the time when we were conducting the interviews. What did these women remember? We wanted to know what was important enough, or transformed their lives profoundly enough, or was wonderful enough, or terrible enough, to be remembered after forty years. Which of those policies and initiatives produced lasting change? Which of them were so disruptive that people remembered them long after they disappeared? What was the relationship between what the state said it wanted to do, and what women remember about what happened, and what they themselves did, in their home communities?

Because we are talking about the relationship between state goals, daily lived experiences, and memory, it is not a matter of whether state ideology, as you put it, instructed women about how to remember things. The interesting question is why women remembered what they did, and how they used the state language of revolution to make sense out of their own memories. If women remembered things that were very different from what state policy or ideology would predict, then I wanted to know why and how that divergence happened.

Let me give you an example. One of the phrases used frequently in state publications is “the old society.” “The old society” is supposed to describe a historical set of social relationships, many of them oppressive to women and exploitative of poor people. The revolution is supposed to bring a clear dividing line between “the old society” and “the new society.” For some communities, the new society officially began during the war of resistance against Japan, in the Communist base areas. For some communities, it happened in 1949, when the People’s Republic of China was established—a date that is called Liberation in Big History accounts. And for some communities, it happened in the early 1950s, when the Party consolidated local control over most of China, and carried out a land reform.

But social change is an uneven process, and it does not necessarily work this way. In the interviews we conducted, everyone knew that Liberation had happened in 1949. but with a few exceptions, most women did not remember anything changing in their villages at the moment of Liberation. Some of them first got involved in activities outside the home as young unmarried women, when members of visiting work teams mobilized them to participate in meetings to criticize landlords during the land reform. Some of these women then learned about the 1950 Marriage Law, went on to break off engagements that their parents had arranged for them. For other women, who were already married in 1949, going out to political meetings meant conflict with their in-laws, who feared that if they ran around outside the home too much, they might decide to seek a divorce. In fact, some of them did just that. For both of these groups of women, new policies brought by the revolution changed their personal lives in dramatic ways. They have a clear sense of a break between “the old society” and “the new society,” linked to events in their personal lives, but that break did not exactly correspond to national regime change. It corresponded to the establishment of new leadership and new possibilities in their own villages.

Another group of women were already adults and experienced farmers before 1949. They continued working in the field after 1949. Their daily activities in the fields did not change. What did change was the social significance attached to those activities. In the 1940s, a woman working alone in the fields was a sign that able-bodied male labor was lacking in the household. The woman might be a widow, or her husband might have been conscripted into the Nationalist army or might have left home to seek work in a nearby city. In any case, the sight of her working in the fields suggested that she was poor, alone, vulnerable, and possibly not virtuous—because what virtuous woman would be seen alone outdoors, where soldiers or bandits and even predatory fellow villagers might find her? Now, in the 1950s, as land reform was completed and collectivization began, a woman working in the fields was a sign of competence and political initiative. Some of these women were identified by Women’s Federation cadres who spent time in rural areas mobilizing rural women. Some became regional or even national labor models, bringing pride and attention to their communities. For them, the line between the old society and the new society took form gradually, as the organization of labor in villages began to change.

When women remembered and talked about their past, they used the terms “the old society” and “the new society.” But often they did not tie them to a specific calendar date, but rather to their own sense of when their own daily lives began to change. As I just suggested, this change looked different depending on where they were, what sort of family they were part of, how old they were, and whether they were married. Also, in memory, sometimes the line between “the old society” and “the new society” was fuzzy. “The old society” referred to a time when life was difficult. “The new society” referred to a time when life got better. But of course, life after 1949 in the villages had its ups and downs too. One particularly difficult time was during the three hard years that followed the Great Leap Forward of 1958-1959. In the area where we interviewed, widespread famine did not occur during this period, as it had in some other places in China. But there were certainly food shortages and other types of hardship. So when some women referred to “the old society” in talking to us, they remembered it as having continued into the early 1960s, when the food supply situation began to improve again. This was definitely not the way official state language talked about the old society, but their usage did express something they had learned from official stage language: that “the old society” was bad and “the new society” was an improvement. They just remembered the important improvement as coming at a different point in time from what the official state timeline said.

I don’t think that there is ever a single person, or even a single state, controlling a memory template. But the state did provide rural people with a powerful language they could use to express what was happening to them. When they did so, many changes occurred in the way they used standard state terms. Those changes are important to understand.

Q :3 Cao Zhuxiang is a widow.Dundian cadres advised her to remarried because remarring is the right of women. But Cao Zhuxiang refused.This is interesting: because forcing women widowed is the persecution of feudal, as a laomo , she should criticize it. However, Cao Zhuxiang established her positive public image because she refused remarriage. How do you see this interesting phenomenon? How did you explain Timothy Mitchell's "national effect" here? Or how to understand "all socialism is local"?

This is a very good illustration of what we were just talking about in the previous question, about how a state category needs to be understood as it interacts with people's social and individual responses. Cao Zhuxiang, as you said, was a widow. She had been widowed years before 1949, and even before that, when her husband was conscripted and away from home, she was one of the women who had to work in the fields by herself. It was very important to her during that period that her fellow villagers should understand that she was still a respectable woman, and was not to be threatened or assaulted because she was out working alone. She made sure that her actions were above reproach and that no one in the community could criticize her for not being a virtuous woman. Later, her husband grew ill and died. She also had two children, who by the time of 1949 were half-grown.

Women's Federation cadres who stayed in the village found that Cao Zhuxiang was very capable and wanted to recommend her as a leader, and somewhat later as a labor model, for her role in growing cotton. In many respects, she was an exemplary woman of the new society: fully involved in collective production and enthusiastic about the state initiatives in the villages. But right after 1949, when Women's Federation work team members spoke to her about whether she would be interested in remarrying, she was definitely not interested. For them, finding a partner of your own choosing, someone to share your life with, was a good thing, and they were startled to find that she was not enthusiastic about remarrying.

There were many different reasons for the way she felt, and it is not clear to me that any of them should be understood in simple ideological terms. As I said, it was important for her own sense of herself to be regarded as a respectable virtuous woman. Before 1949, she had gone to a lot of trouble to safeguard her reputation, even though she had to work in the fields. But I think in some ways the question of virtue was the least important factor, and we did not see any sign that she was interested in a traditional notion of widow chastity.

For her, marriage had never been a matter of companionship or personal compatibility. She appeared to get along with her husband well enough, but she was older than he was, he had still been a young adolescent when she was brought into the family as his bride, and soon after he became a full-fledged adult he was conscripted, taken away, later got ill, and died. So she was used to being on her own, and probably did not understand marriage to be an arrangement that had anything to do with personal or emotional satisfaction.

She also had a keen sense of responsibility to her children. Since they were members of her husband's family, she knew that if she remarried, their claim on the family land would quite possibly be threatened. This was before the land reform. She was also determined to bring up her son to carry on her husband's family name. Of course, one can call this a "feudal" attitude, that one should carry on the patriline of one's husband. But it was also a practical matter of her children's well-being and the survival of all of them, which depended on the land. Even though, after 1949, with land reform and collectivization, it was no longer possible for the kinsman of her husband to push her out of the family and take her children’s land if she remarried, she was still determined to continue to bring her children up until adulthood and for her son to become his own head of household. In her mind, all this would be simpler if she did not remarry.

So you can say that Cao Zhuxiang showed a combination of older attitudes about her duty, a sense of independence and her own capability that was produced by the difficult situation she found herself in before 1949, and also the sense that now, after 1949, the security situation was better and she in fact did not need to rely on a man to keep her safe. All of these things combined to make remarriage not look attractive or necessary to her. On top of that, she felt that now that her children were partly grown and did not need her attention every minute, she could devote herself to working as a farmer and improving the livelihood of her family. She saw participation in collectivization as a means of making her family’s life better.

In a way, her status as a widow made her more available to be a labor model and someone who could become deeply involved and collective production. Because her personal virtual was beyond question, she met the criteria that the state also required of labor models. They did not want to publicize anyone as a model if that person had a complicated personal life that might bring them criticism, and in the process damage the local prestige of the state. So Cao Zhuxiang met that category as well.

You asked about Timothy Mitchell's notion of the "state effect." By this I mean the following. Mitchell is saying that there is not a natural line between "state" and "society." The idea that the state stands above society, and is separate from society, is a somewhat recent one. Mitchell says that the world appears to be divided. On one side appear people and their daily activities. On the other side appears a state structure that looks like it stands above individuals and exists without them. But actually, the state is also produced by individual (and collective) human activity. There is no clear binary between an abstract state on the one hand and individuals on the other. But there are daily practices that make it appear as though this division exists. It takes a lot of work to make it seem as though state and society are completely different things. Meanwhile, in the gray zone where they are entangled, a lot of activity goes on. Although Mitchell was talking about the Western world after World War II, I have found his work useful in thinking about the situation of labor models under socialist collectivization in China in the 1950s. Labor models were named by local cadres, but they belonged to both to the state and to society, and they operated in the zone where the two were entangled. Cao Zhuxiang was an important actor in the activity in that zone.

As for "all socialism is local," here I just want to call attention to the fact that it is not a matter of the state saying something and everyone all over the country understanding it or experiencing it in exactly the same way. Socialism took shape through local leadership. The state was not homogeneous. It consisted of many levels. Cao Zhuxiang was one face of the state. People understood state policies through watching her actions and listening to what she had to say. In other communities, the shape of socialism and the way its goals were pursued were also affected by local officials. And socialism is also a local because the basic circumstances differ a great deal from one region to another. Therefore, I think we can use the term "socialism" as a kind of shorthanded, but we always have to stop and ask: what did socialism mean in this particular community?

Q:4 During 1950-1960,China was carrying out socialist revolution and transformation and the whole society was full of male characteristics. The class is eliminated.The difference of sex also is eliminated. The women are treated as same as the man. How do the women (interviewee) understand this and how do the male society influenced the women’s lives(72 interviewees)? Such as mother, what is the characteristics of the role of mother during this time ?

A : I am not sure that I would call China a "society full of male characteristics" at this time. It is true that people were called upon to put forth heroic efforts in the course of collectivization and during the Great Leap Forward. It is also true that much of that heroism involved activities outside in the fields, rather than in the home. But the idea that heroism is a purely male characteristic is itself the result of a particular historical process. There is not anything "natural" about equating heroic effort primarily with men.

Also, I do not think that class was exactly eliminated. Everyone had a class label, for instance "landlord" or "poor peasant," and those class labels helped to shape people’s daily lives and marriage prospects, even though there were no actual landlords anymore. There were also new emerging class differences, perhaps between cadres and ordinary people. And there were also important differences emerging between the city and the countryside. So there was continued struggle of all kinds, but because the class labeling system described a version of social relations from before 1949, it was not very useful for describing these new divisions and struggles.

It is not the case that women were treated as the same as men. Women had equal political rights with men, and that was a real achievement of the People’s Republic of China, something that the Nationalists had hoped to achieve but had not been able to accomplish. However, in the countryside, women were not treated the same as men. Under collective agriculture, when a man went to the field to work for a full day, he usually earned 10 work points or more. When a woman went to the fields for the day, she usually earned seven or eight. This was true even if they were doing the same tasks, such as weeding or picking tea or picking cotton. And most of the time, men and women were not doing the same tasks. Most technical tasks were assign to men. Increasingly across the collective period, more and more of the basic agricultural work was done by women.

One of the reasons that women earned fewer work points than men is that most people in the villages agreed that men's labor was worth more than women's, even though sometimes younger farming women would argue that this was not fair. Another reason was that married women had a very heavy domestic burden. They came to the fields later than men, because they made breakfast first. They left the fields earlier, because they had to go prepare lunch. They had very heavy child care burdens. They had to make all of the cloth and clothing and shoes that their growing families needed. They did most of this needlework at night, after everyone else was asleep, and they did not get paid for it. Of course, if they had not done this work, people would not have had clothing to wear to the fields or to wear to school. In that sense, the domestic labor of women was absolutely essential to the development of the economy. But it was not remunerated labor. Only the work points they earned in the fields were remunerated.

The fact that fewer children died at birth, and that the public health and security situation improved in the 1950s, meant that more children survived than they had in earlier periods. This meant that more children had to be fed and clothed. you might say that the life of a mother in the collective period, even though it was free from marauding soldiers and bandits compared to earlier times, was in some ways quite difficult. Partly because state policies were in fact successful in reducing mortality and increasing production, there was always more work to do. Women did not sleep enough because of the second shift of domestic work. That is one of the reasons that some of their memories of the collective era are blurry.

5 Q: What are the difference between the women’s memory/the gendered memory and main history/man history in this book? (What is the characteristics of women in their memories?) What is the difference between women’s sense of temporality and men’s sense of temporality?

AlFirst of all, I want to make it clear that I do not think there is any "natural" difference between men's and memories and women's memories. Also, Gao Xiaoxian and I interviewed far more men than women, for the simple reason that women tend to live longer than men in the villages, and there were far fewer men to interview. Also, we were primarily interested in the experiences of women, so even if more men have been alive and able to talk to us, I am not sure we would have tried to design a completely gender-balanced sample.

All that said, women do remember different things about the collective than men do. I think that is because women had different daily experiences from those of men during that period. For the reasons I just described, they worked a double shift, while their work for the collective in the fields was consistently paid less than that of men. Another result of women's double burden was that they tended to be less involved in village leadership than men were, and went to fewer political meetings at night. There were many individual exceptions, of course, but I think it is possible to say that most women were less directly involved in listening to local political briefings or attending party meetings than men were.

This meant that when we talked to men, the men's stories were far more likely to be expressed in standard Party language, with the names of various campaigns, calendar dates, and slogans attached to the different campaigns. With women, however, they often recalled some elements of the campaigns, but they did not necessarily put them in chronological order. Sometimes, they would take the elements of a campaign and disaggregate it into aspects that affected their daily lives. For instance, they all understood the term "Great Leap Forward," but when they themselves spoke about it, they said "the time when we ate in the dining halls." This was something that had a fundamental effect on their daily lives, and so they named the campaign according to what its most prominent element was for them.

Another thing about temporality has to do with how women organized their memories. Most of them could remember the names of the various campaigns, but they often scrambled the order in which the campaigns happened. However, if you asked a woman, "how old was your son when thus-and-such a campaign happened?", then she would generally be able to answer. The answer became even clearer if we said, "under what zodiac sign was your son born?" They could all answer that question. Then it was possible for us to match the answers that they gave to various calendar years. I don't know if men would have organized their sense of time according to the birth of their children. Perhaps some of them would. But I do know that the men we talked to also had a standard political timeline in their heads, and many of the women did not. I think one need not look any farther than the profoundly gendered nature of experience in Chinese villages during the collective period to understand why this was the case.

6 Q: what is women’s role in socialism, and how/why is socialism gendered? “pitiful”(keliande) repeats lot in their narratives, how do you think about this word?

A: I think I have answered much of this question already. One thing I want to emphasize about women's role in socialism in the Chinese countryside is that economic development in the Mao years absolutely depended not only on women's labor in the field, but also their reproductive labor in the household. Socialism was partly gendered, as I just said, because there was always a gendered division of labor, even though the tasks considered appropriate for men and for women respectively kept changing. For instance, women began on a regular basis to cultivate cotton, to plow fields, and to do many other tasks that had previously been regarded as the work of men. At the same time, men moved out into new tasks, such as dam construction during the Great Leap Forward, tractor repair or chemical fertilizer production in the 1960s and 1970s, and contract labor in nearby cities whenever there was a labor shortage in industry. The idea that gender was an appropriate way to sort those tasks remained a very powerful idea across the entire period. That means that women often did different kinds of work from men. And because some of the work they did happened in households late at night, their double day also affected their participation in collective labor during the daytime, and limited their involvement in the kind of political work that structured power relationships in rural communities. Although some women became important local village leaders, in fundamental ways their experience was different from that of men.

As for the term “pitiful,” I think that women use it in at least three important ways. The most standard way is to describe their situation before 1949, when many of them became refugees on the road or lived in families under conditions of extreme poverty, or fled into the hills to evade bandits, or hid themselves at home to stay clear of troops who might sexually assault them. Looking back from the vantage point of relative security during the collective period, women called the pre-1949 situation pitiful.

A second way that they used the term pitiful was to refer to all of the labor they had to perform during the collective period. Many of them were conscious of the fact that having so many children, a situation that they could not really control because reliable birth control was not available, made their lives much harder. And although they did not say so directly, the fact that farmers remained poor relative to urban people throughout this whole period, and suffered through the results of policies that went awry such as the Great leap Forward, also seemed pitiful to them when they looked back on their adult lives as rural laborers.

Finally, a third way in which some of them used the term pitiful was to refer to their situation in old age, during the reform era. Conditions of support for the elderly are not stable, and many of their children, who are now middle-aged themselves, have their own economic burdens and do not always reliably support or care for their aged parents. So there is a pervasive sense in their comments that the term pitiful, although it may apply to the distant past, also applies to the recent past and in some respects to the present.

7 Q: You said gender “ needs to be understood as one in an array of powerful relationships”(287).Would you like explain more about this?

A: As I'm sure you can tell from looking at my book, I think that gender is an extremely powerful tool of analysis. It can be found everywhere, and it is an important basis for making social and cultural distinctions. However, it is certainly not the only variable that we need to pay attention to if we are trying to understand how a society works. In the case of Chinese villages in the 1950s, we certainly need to look at class, even though the system of class labels was not a very good descriptor of current social relationships. We also need to pay important attention to regional differences. And we need to note that people of different generations had different attitudes toward the policies brought by the new People’s Republic of China. For instance, many younger women embraced the promise offered by the new Marriage Law. But older women, who were already mothers-in-law and had sacrificed for a lifetime to be able to accumulate enough resources for their son to bring in a bride, were often vehemently opposed to the law because it permitted women to divorce. And, of course, differences in individual character and temperament also affected how people responded to the changes of the collective period. We must pay attention to how gender interacts with other axes of difference in particular historical situations.

8 Q:What is gender?( Joan Scott) what is the difference between a gender work and a historical work? How does this book use the theory of Gender?

A: I am skipping this question. I think I have said enough about gender in this interview already. Joan Scott’s work has been translated into Chinese, as have many other works discussing gender as a category of analysis. If you want to recommend to readers a discussion of the way gender has been used in Chinese historical studies see my article with Wang Zheng, in Chinese and English:

“Chinese History: A Useful Category of Gender Analysis,” co-authored with Gail Hershatter, The American Historical Review, Vol. 113, No. 5, December 2008, 1404- 1421.

中国历史:社会性别分析的一个有用的范畴“Zhongguolishi: shehui xingbie fenxi de yege youyong de fanchou,” a Chinese version of the article co-authored with Gail Hershatter, Social Sciences [Shehui kexue], No 12, 2008, 141-154.

9 Q:The materials of the book Dangerous Pleasures: Prostitution and Modernity in 20th-Century Shanghai is mainly from official document or man history. It is a narrative history of prostitution rather than a prostitution history.

The material of this book is mainly from women themselves. but how do you balance the objectivity of history and the subject consciousness of women? Do you think the book re-build a history? Except for 72 women’s narrative, do you use any other “dry facts”,such as statistics, annals, and official documents?(i saw some statistics in the book )As a historian, did you ever think about what is objective history?

A:First of all, I don't think there is such a big difference between the methods of my book Dangerous Pleasures and the methods of The Gender of Memory. In each case, a historian has to work with the kinds of materials that are available to her. For various reasons, it was difficult for me to do oral histories with former prostitutes, and in any case for the late 19th century and much of the Republican period, the people involved were no longer alive by the time I began my research in the late 1980s. In the case of prostitution, however, there were many written materials about prostitution from the point of view of reformers, police, revolutionaries, feminists, and others. So the book might not have had as many direct testimonies as I would have liked, but it was still a history of prostitution.

In the case of The Gender of Memory, it is true that the core materials were the interviews that Gao Xiaoxian and I conducted. Each of these 72 women offered a rich narrative account of her own life. However, we also spent many hours collecting materials from the provincial and county archives, and I also did a great deal of research on the secondary literature produced by Chinese historians about the collective period. Without that contextualizing material, the oral narratives by themselves would have made for a colorful, but in many ways confusing, account. So yes, I used statistical materials, government reports of all kinds, local gazetteers, newspapers, and other people’s published scholarly writings as well as the interviews.

But I also tried to think critically about the memories of these women. When they remembered something, I asked myself why it was important enough for them to remember one story or one detail or one set of feelings, out of all of the memories they could have recalled from their daily existence. What made some events or people stand out in memory, while others were forgotten? I also asked myself women’s understanding of their own pasts had changed, based on the way their lives had gone after the 1950s. Memory has to be approached critically, the same as any other historical source. It is not more “true” than other sources, although it may allow us to get at different aspects of the past.

I do not think that “objective history” is the most useful way to describe the goal of the historian. I do not think that there is one single truth about "how things were." It depends on where you were at the time, and who you were. This is true of oral narratives, and it is also true of written historical materials. However, as the American historian Linda Gordon once said, "Just because there is no single truth does not mean that there are no lies." The biggest challenge is to establish facts, and then explore the many meanings that people attached to those facts at the time, and have attached to them in retrospect. The challenge for a historian is to reconstruct the circumstances under which history gets made, and also the circumstances under which it is remembered.

10 Q: Your Chinese women study is unique. why are you interested in this? What is the greatest impact on your academic path?

A:Like everyone else, I am a product of a particular time and place. I came into “the China field” as a college student, in years marked by the Vietnam War and the antiwar movement, Nixon’s China visit and the late Cultural Revolution, the move toward people’s history and the feminist imperative to “make the invisible visible.” Research interests first formed in that era have engaged me for many years, even as political and academic contexts have changed my approaches to them. In writing about early twentieth-century workers, young women in the reform era, prostitutes before and after the 1949 revolution, and rural women’s memories of collectivization, I find myself circling back to certain formative questions: what counts as an event? Who gets to decide? How is the historical record shaped in interactions with the present moment? What are the obligations of a scholar working in North America to her own students, to the people she studies, and to the larger world beyond? We know that ignoring history can result in terrible consequences—but how should we pay attention to history, and what lessons and opportunities for critical reflection should we draw from it? Those are the questions that continue to fascinate me—and today, when much history is forgotten, neglected, and even suppressed in many different part of the world, those question are more urgent than ever.